What Can The Antibiotic Shortage Teach Us About Weathering API Supply Disruptions?

By Nicole Reynolds, Clarivate

Potential drug shortages have made headlines recently with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, with manufacturing companies contending with government-mandated or recommended temporary shutdowns, new safety initiatives to ensure employee health and well-being, employee absences due to illness, and restrictions on importing/exporting and travel. While it is impossible to prepare for every worst-case scenario, a catastrophe such as this or an environmental disaster can occur at any time, disrupting manufacturing processes. Preparing for the unexpected, including establishing a reliable set of global active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) suppliers, can minimize the impact.

Underlying Reasons For Antibiotic Shortages

The current situation is not novel. In the United States alone, there were 148 antibiotic shortages from 2001 to 2013,1 and a recent penicillin shortage affected at least 39 countries throughout Europe, the Americas, and Asia.2 As of June 29, 2020, 10.5 percent of all drug shortages listed by the FDA were antibiotics.3

To get to the core of why and how supply is being disrupted, organizations ranging from the nonprofit Access to Medicine Foundation4 to the FDA5 have conducted exploratory projects, including interviews with industry stakeholders.

First, the profit margin for antibiotics is narrow – throughout the supply chain – resulting in few manufacturers for a given API. For them, constraints on manufacturing capacity force decisions about the best use of their available resources.5 The most profitable choice often wins.

These issues are compounded by a lack of incentives for robust quality management systems. Some manufacturers find it difficult to justify the high cost and risk of investing in equipment expansion or upgrades. Older, poorly maintained manufacturing equipment can lead to quality problems and ultimately, a shortage in the API supply. According to data from the FDA, older drugs, with a median time of nearly 35 years since first approval, represent a large proportion of drugs in shortage.5 The report concluded that, as facilities age after first approval, the following factors contribute to quality issues: lack of updates to routine operations to maintain a state of control, older technology, and changes in suppliers and scientific expectations.

Finally, disruptions such as an outbreak or natural disaster tend to upend the market due to logistical and regulatory issues. Because there are typically few active suppliers for a given API, when one stops production, output from the remaining suppliers needs to increase exponentially to meet demand. Increasing production can involve additional approvals from multiple regulatory agencies, requiring significant resources.

In an effort to help API manufacturers and pharmaceutical companies address these issues and minimize the risk of drug shortages, the FDA and International Council for Harmonisation (ICH)6 have issued or are expected to issue guidelines to improve quality controls and provide reasonable expectations for the level of regulatory review required when scaling production to meet increased demand.

Characteristics Of Antibiotics Manufacturers

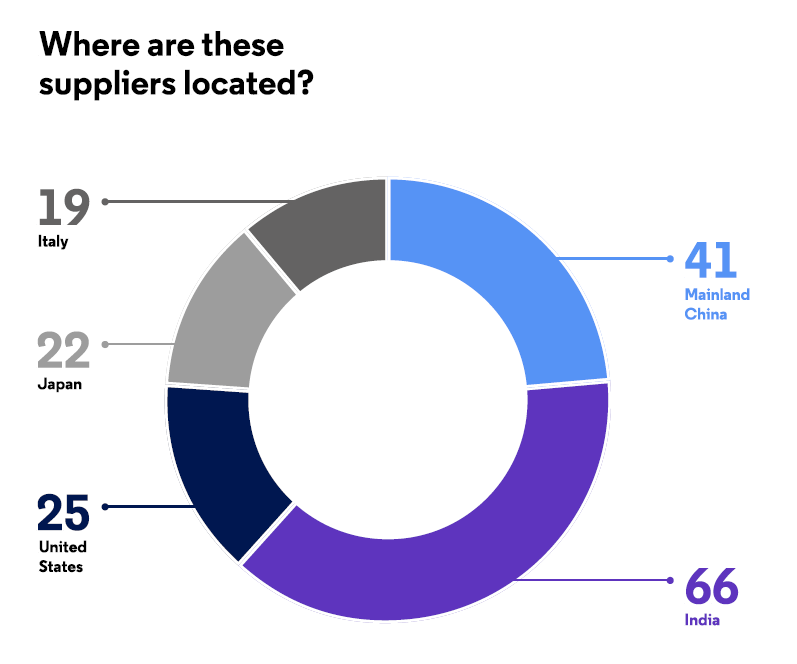

The effects of these challenges are reflected in the characteristics of global antibiotic API suppliers, of which there are currently slightly more than 1,200. Of these, 182 companies are rated as “established,” with many years of experience supplying large numbers of APIs to highly regulated markets such as Europe, North America, and Japan. “Less established” companies (76 companies) tend to have few products or limited experience supplying APIs to these markets. The majority of these manufacturers have corporate locations in India (26 percent), mainland China (16 percent), the U.S. (10 percent), Japan (9 percent), and Italy (7 perceent).7 See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Location of established and less-established antibiotic API manufacturers

The 309 companies with “future potential” have an interest in supplying to regulated markets and are therefore expected to continue developing their capabilities and reach the “less established” rating within a few years. In the meantime, they have limited or no known performance capabilities. “Local” companies include the 555 organizations that can supply only to their local and other less-regulated or unregulated markets.

Therefore, only 25 percent of antibiotic API suppliers have the capabilities to meet the demand of the regulated market, which should be considered when establishing a reliable backup plan. It will be important to establish relationships with these suppliers early, before competitors have a chance to, and consider expanding manufacturing partners to new regions to increase the availability of supply.

Varying Supplier Availability

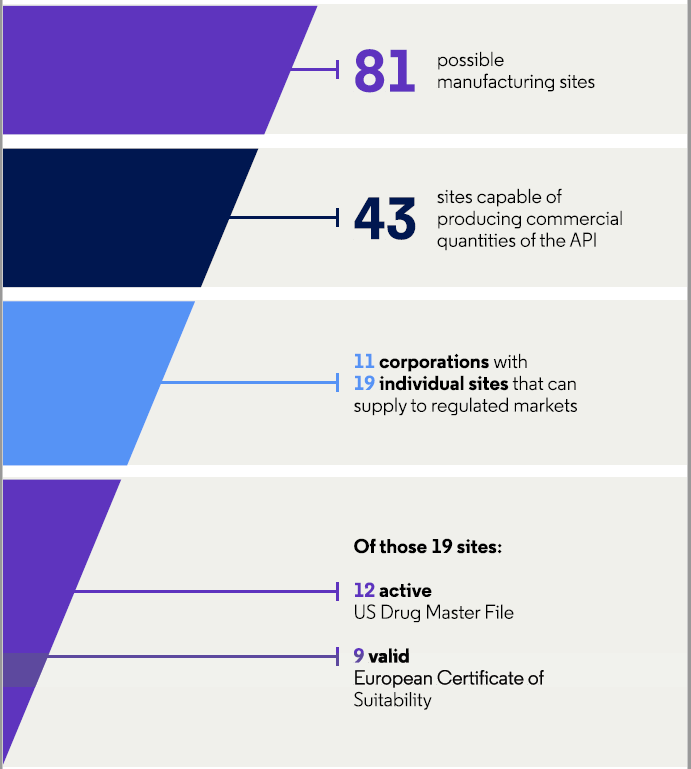

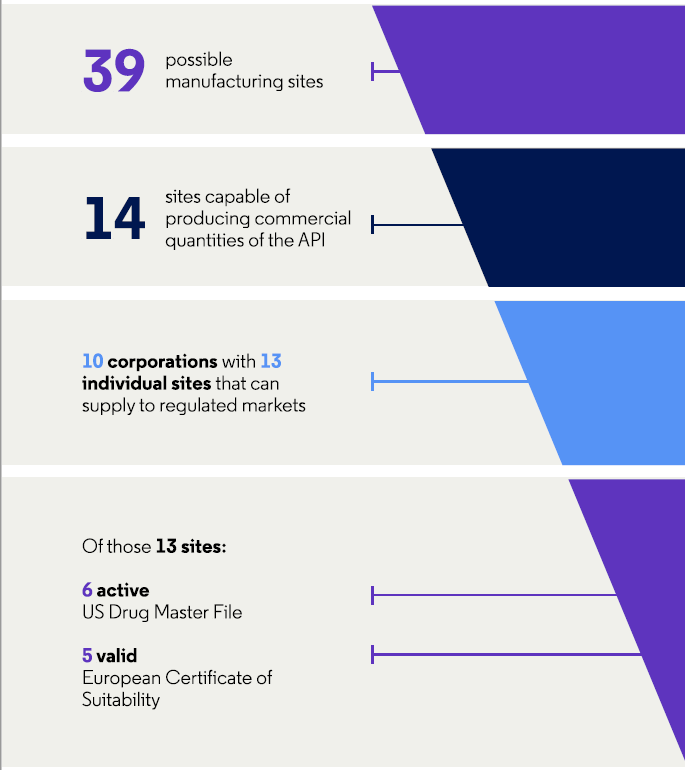

Availability also depends on the specific API. For example, a recent analysis of API suppliers for azithromycin or cephalexin revealed that there are 81 possible manufacturing sites for azithromycin but only 39 for cephalexin.7

Of the 81 sites for azithromycin, approximately half (53 percent, 43/81) are capable of producing commercial quantities of the API, while only a quarter (24 percent, 19/81) can supply to regulated markets (Figure 2). These 19 sites are in India (47 percent, 9/19), mainland China (16 percent, 3/19), Spain (16 percent, 3/19), Israel (11 percent, 2/19), Croatia (5 percent, 1/19), and Malaysia (5 percent, 1/19).

Figure 2: Characteristics of API manufacturers for azithromycin

Regarding cephalexin, 36 percent (14/39) of the sites are capable of producing commercial quantities of the API and a quarter (33 percent, 13/39) can supply to regulated markets. These 13 sites are in India (15 percent, 6/39), mainland China (5 percent, 2/39), Italy (5 percent, 2/39), Brazil (3 percent, 1/39), Spain (3 percent, 1/39), and Taiwan (3 percent, 1/39).

Figure 3: Characteristics of API manufacturers for cephalexin

Additional comparative analyses regarding amoxicillin and piperacillin/tazobactam also identified a large gap in the number of manufacturers – 125 for amoxicillin and 27 for piperacillin/tazobactam.8 For the former, the API suppliers are located in China (45 percent, 56/125), India (20 percent, 25/125), Europe (14 percent, 18/125), the U.S. (14 percent, 18/125), and other countries (7 percent, 9/125). When the authors evaluated the situation earlier in the supply chain, companies in China provide 80 percent of the raw materials, while companies in India provide 20 percent of the raw materials, demonstrating a dependency on a limited geographic area.

Similarly, the API suppliers of piperacillin/tazobactam are located in China (59 percent, 16/27), Europe (19 percent, 5/27), India (15 percent, 4/27), and other countries (7 percent, 2/27). And companies in China provide approximately 90 percent of the raw materials, while companies in India provide the other 10 percent.

Not only is the current situation important when determining a reliable backup plan, but you also need to look at the future competitiveness of the antibiotic market to determine the availability of a specific API. Of the 16 antibiotics set to go generic over the course of 2021, there are varying levels of API availability for the top six (based on worldwide sales).7 Of these six, colistimethate sodium and aztreonam lysine are excessively available, daptomycin is available in regulated markets, ceftaroline fosamil is available in less regulated markets, and there are limited sources for fidaxomicin and bromelain.

These examples highlight the varying situations for each API as well as the dependence of the industry overall on a very narrow global footprint. Shutdowns or disaster-related damages in Asia, for example, could severely reduce the supply of antibiotic API around the world.

Establishing A Reliable Set Of API Suppliers

It is important to consider a range of manufacturer characteristics to create a sound supply chain with alternate suppliers on deck.

Given your current and intended markets, evaluate the manufacturers for the following:

- Do they have the appropriate regulatory holdings and a clean inspection history in those areas?

- Have they maintained the required regulatory approvals?

- Beyond current good manufacturing practices (CGMP) to meet the minimum thresholds for equipment, facilities, production, and quality systems, have robust quality management systems that incorporate a quality culture and proactive issue detection and resolution been established?

- Does the facility have the manufacturing capacity to produce the required volume of API, and are there other competing APIs manufactured within the facility that might take precedence over your API of interest?

- To minimize the effect of an unexpected situation in a single geographical area, is the supply of raw materials from multiple locations?

- Are they located in separate geographic areas?

- Do they have appropriate packaging and stability controls to be able to distribute API across disparate climates, geographies, and more?

It is also worth broadening the evaluation beyond specific manufacturer characteristics to your sourcing strategy. Do you have supplier options in different geographic locations? Is it worth having local manufacturing options for final formulation in specific markets, to contribute stability and help assure an uninterrupted supply?

Preparedness Is Key

With appropriate planning, the effects of API supply disruptions can be minimized. As with many aspects of pharma, ensuring quality while maintaining diversity are key. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need to reevaluate API manufacturing partners, and we may see companies shift to a more regionally diverse supply chain, including an appropriate mix of localized and global capabilities to meet specific market needs. Simultaneously, we could see API manufacturers diversifying their site locations to minimize the impact on income streams if issues occur in a specific region by continuing manufacturing at sites in other locations.

References:

- Quadri F, Mazer-Amirshahi M, Fox ER, et al. Antibacterial drug shortages From 2001 to 2013: implications for clinical practice. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:1737–1742.

- Nurse-Findlay S, Taylor MM, Savage M, et al. Shortages of benzathine penicillin for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of syphilis: An evaluation from multi-country surveys and stakeholder interviews. PLOS Med 2017;14:e1002473.

- FDA Drug Shortages. Current and resolved drug shortages and discontinuations reported to FDA. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/drugshortages/default.cfm. Accessed 6/29/2020.

- Cogan D, Karrar K, Iyer JK. Shortages, stockouts and scarcity: The issues facing the security of antibiotic supply and the role for pharmaceutical companies. Access to Medicine Foundation. May 31, 2018. https://accesstomedicinefoundation.org/media/uploads/downloads/5bea831e16607_Antibiotic-Shortages-Stockouts-and-Scarcity_Access-to-Medicine-Foundation_31-May-2018.pdf. Accessed 6/29/2020.

- FDA. Drug shortages: Root causes and potential solutions. A report by the Drug Shortages Task Force. 2019. fda.gov/media/131130/download. Accessed 6/29/2020.

- International Council for Harmonisation. Technical and regulatory considerations for pharmaceutical product lifecycle management: Q12. November 20, 2019. https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/Q12_Guideline_Step4_2019_1119.pdf. Accessed on 6/29/2020.

- Clarivate. Cortellis Generics Intelligence. Analyses completed June 11, 2020.

- Granada AG, Wanner P. Managing supply chain sustainability risks of antibiotics: A case study within Sweden. Master’s thesis. June 2019. Available at: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1342267/FULLTEXT01.pdf. Accessed 6/29/2020.

About The Author:

Nicole Reynolds has worked within the pharmaceutical industry for over 20 years. Leveraging competitive intelligence, translational research, regulatory intelligence, and generics intelligence, she partners with life science companies across the globe to understand their challenges, guide them through the intricacies of the pharmaceutical industry, and connect them with best practice solutions to meet their needs. Reynolds holds a masters degree in science education from Widener University.

Nicole Reynolds has worked within the pharmaceutical industry for over 20 years. Leveraging competitive intelligence, translational research, regulatory intelligence, and generics intelligence, she partners with life science companies across the globe to understand their challenges, guide them through the intricacies of the pharmaceutical industry, and connect them with best practice solutions to meet their needs. Reynolds holds a masters degree in science education from Widener University.