Supply Agreements — Removing The Stress From 'Failure To Supply' Negotiations

By Hal Craig, founder, Trout Creek Consulting, LLC

The failure to supply (FtS) provision in a drug product or drug substance supply agreement – typically ranging from a paragraph to a couple of pages – can be the most hard fought over “what if” in the agreement and, after price and volume, the section of an agreement with a high potential to fracture a customer-supplier relationship. Part 1 of this two-part series addressed general industry and supplier perspectives that can complicate FtS negotiations. This article addresses the drug marketer’s perspective and provides a path forward to negotiate a mutually agreeable solution.

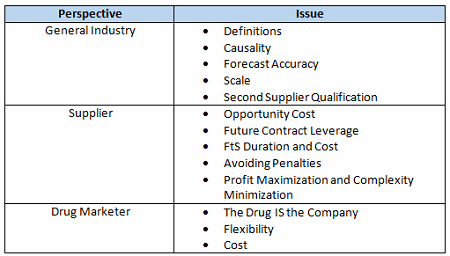

Table 1 summarizes the complicating issues that can make compromise difficult without trust.

Table 1: FtS Provision Complicating Issues

Issues That Complicate FtS Negotiations From A Drug Marketer’s Perspective

The Drug IS The Company

For many development and early commercial-stage drug marketers, their lead drug may be the only product the company has or the only product likely to reach market for a couple of years or more. The drug marketer’s financial viability and its potential to be acquired, out-license, or enter into an IPO may depend on the commercial success of its lead drug. Furthermore, the early commercial-stage drug marketer will likely have a sole-sourced supply chain. Hence, the drug marketer wants contractual assurances that the CMO(s) and other suppliers are committed to delivering drug product on schedule, in specification, validated, and produced per cGMP and the quality agreement. In short, the drug marketer wants to be a priority for its supply chain partners. If profitable revenue is the carrot to suppliers, then the FtS provision is the stick.

Flexibility

Forecasts of development and early commercial-stage drug marketers are heavily impacted by both the funding and regulatory environments that the company faces. This impacts both the pace of activity and the ability to make financial commitments to inventory, capacity, people, and other items. Development and early commercial-stage drug marketers also desire supply agreements that don’t limit future deals — acquisition and licensing — by imposing too many manufacturing and financial restrictions on potential acquirers and licensees. Although having said this, there are acquirers and licensees who prefer that the drug developer has contracted the supply chain before the acquisition or license is done. Interestingly, some suppliers may be concerned about setting an FtS provision precedent with original drug marketer A that could haunt them in the future if another of their customers, drug marketer B, buys A and then presses to have the “best” FtS provision harmonized across the products made for A and B.

Cost

Different drug products face different competitive dynamics and cost pressures. Novel biologic and small molecule therapies that represent a significant improvement in the standard of care may give the drug marketer different economics than a generic or OTC drug product would. The drug marketer doesn’t want to absorb additional costs associated with an FtS for reasons that are within the supplier’s control. While not strictly related to FtS, drug marketers want to see improved economics in their supply chain.

Is There A Less Stressful Way To Arrive At A “Failure to Supply” Provision?

Of course there is!The path forward starts with all parties recognizing six key points:

- It’s About the Patients: The overarching objective is to reliably supply life-improving therapies to patients — whether the life-improving therapy is a new small molecule or biologic product, a lower-cost generic product, or an OTC product. Patients should not face drug shortages and interrupted therapies.

- Mutual Need: The drug marketer and its supply chain partners need each other to be successful.

- Prudence: The drug marketer (and hopefully all parties in the supply chain) will practice prudent supply chain practices to ensure that patients are reliably supplied and that the P&L is protected from risk.

- Trust: The drug marketer has (or should have) chosen its lead suppliers — CMO, API, third-party logistics, and others — for a very important reason: It believes they are the first choice suppliers it can win with. The drug marketer has (or should have) selected these suppliers against a range of metrics — product/service offering, cost, cGMP history and practices, reliability, talent, and culture, to name a few — and isn’t looking to change a supplier unless there’s an issue. In short, the drug marketer is starting out with a positive impression of, and trust in, its suppliers.

- Execution: The drug marketer should recognize that if its forecasts are untimely or inaccurate, if its orders are placed late, or if it fails to invest in inventory of long-lead raw materials or raw materials subject to seasonal supply or other disruptions, then the drug marketer risks an FtS.

- Commitment: The supplier’s role is to supply. If a supplier wants a very large or exclusive supply position with a drug marketer — if a supplier wants the drug marketer to “bet its business” on that supplier — then it is incumbent on that supplier to commit to reliably supply, control what is within its control, and accept a smaller supply position if it fails to meet its commitments. A commitment to deliver goes hand-in-hand with a large supply position.

What Might An FtS Provision Look Like?

The specifics of the FtS provision will vary with each drug product because the Definitions, Causality, Scale, and Second Supplier Qualification sections can vary based on the raw materials, technology, shelf life, regulations, supplier location, and other factors associated with each drug product.However, keeping the six key points in mind, the FtS provision might cover the following:

- A determination and explanation of the definitions and causality specific to the drug product

- The ability for the drug marketer to validate commercial supply at a second source

- Sufficient annual production, for commercial sale, at the second source to keep it “qualified”

- The ability to transfer inventory, documentation, methods, and intellectual property, as needed and as permitted by regulation, from the lead supplier to the second supplier to minimize the impact of an FtS on patients by minimizing the time required to bring the second supplier onstream

- Allocation of the cost to mitigate an FtS between the drug marketer and the supplier; cost items to consider range from the incremental cost to acquire spot-market API to the cost of shipping inventory from the lead supplier to the second supplier and are situation-dependent

- If the supply interruption is beyond the reasonable control of the lead supplier, then the lead supplier should contractually be able to return to its primary supply position at a practical time after its production has been restored.

- If the supply interruption is within the reasonable control of the lead supplier, then the drug marketer shouldn’t be obligated to restore the primary supply position at a later date. In essence, if there is an FtS for reasons within the control of the lead supplier, then the lead supplier has, consciously or not, chosen to create an FtS.

Final Thoughts

A successful failure to supply provision requires two things: (1) thinking through ahead of time what the drug marketer and supplier will do if there is an FtS to make it easier to work through the FtS; and (2) highlighting what the drug marketer and supplier should each do to avoid an FtS. The drug marketer should regularly update its forecast and place orders per the supply agreement. The supplier should manage its supply chain, resources, and production schedule to meet supply commitments. Both parties should communicate with each other regularly and consistently. And remember, the goal is making sure patients receive life-improving therapies when they need them.

About the Author

Hal Craig is the founder of Trout Creek Consulting, LLC, a strategy and life science supply chain consultancy focused on solving CMC, outsourcing, strategy, and technical challenges. Clients include venture-backed, family-owned, private equity-owned, and publicly traded companies. Craig serves on the Physical Sciences Investment Advisory Committee of Ben Franklin Technology Partners of Southeastern Pennsylvania. He has a BSChE from the University of California, Berkeley and an MBA from the University of Michigan. He can be reached at hcraig@troutcreekconsulting.com.

Hal Craig is the founder of Trout Creek Consulting, LLC, a strategy and life science supply chain consultancy focused on solving CMC, outsourcing, strategy, and technical challenges. Clients include venture-backed, family-owned, private equity-owned, and publicly traded companies. Craig serves on the Physical Sciences Investment Advisory Committee of Ben Franklin Technology Partners of Southeastern Pennsylvania. He has a BSChE from the University of California, Berkeley and an MBA from the University of Michigan. He can be reached at hcraig@troutcreekconsulting.com.

Disclaimer: This article is intended to provide general information on a particular subject or subjects and is not an exhaustive treatment of such subjects. Accordingly, this article does not constitute legal, accounting, tax, investment, consulting, or other professional advice or services. Before making any decision or taking any action that might affect your personal finances or business, you should consult a qualified professional adviser. In no event will Trout Creek Consulting, LLC or the author be held liable in any way to the reader or anyone else for any decision or action taken based on this information, or for any direct, indirect, consequential, special, or other damages claimed by the reader or anyone else based on this information.