FDA's Drug Shortages Root Cause Report: Does It Miss The Mark?

By Ben Locwin, Ph.D.

The average person in the United States spends $1,200 on their prescription medications annually (Bloomberg, 2019), and that comes in the form of 70% of the population taking at least one prescription medication, and 20% taking 5 or more. Additionally, more than 500,000 people (real people) in America spend over $50,000 on medicines annually. It’s no surprise, then, that when political election cycles renew, one of the top issues of concern every time is the cost of healthcare, which is usually — and myopically — reduced to the shorthand of “drug prices” as a literary proxy for “healthcare expenditures.” These healthcare expenses could indeed have been pharmaceuticals, but they just as likely could have been diagnostics (MRIs, mammography, X-rays, etc.) or medical devices (because even tongue depressors are medical devices) included as part of the repertoire of patient care and treatment.

and that comes in the form of 70% of the population taking at least one prescription medication, and 20% taking 5 or more. Additionally, more than 500,000 people (real people) in America spend over $50,000 on medicines annually. It’s no surprise, then, that when political election cycles renew, one of the top issues of concern every time is the cost of healthcare, which is usually — and myopically — reduced to the shorthand of “drug prices” as a literary proxy for “healthcare expenditures.” These healthcare expenses could indeed have been pharmaceuticals, but they just as likely could have been diagnostics (MRIs, mammography, X-rays, etc.) or medical devices (because even tongue depressors are medical devices) included as part of the repertoire of patient care and treatment.

On the moving frontier of healthcare at the moment, there exist our current cell therapies and gene therapies, whose approval track records currently stand at five for cell therapies and two for gene therapies. These can cost several hundred thousand dollars per patient for treatment. For example, Yescarta (Gilead/Kite) clocks in at $373,000 to treat a patient and Kymriah (Novartis) costs $350,000 to $475,000 per patient.

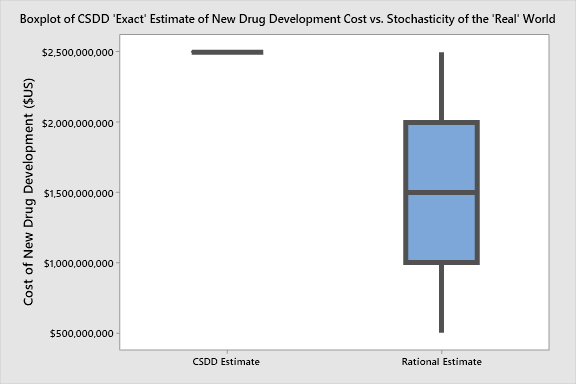

The Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development (CSDD) has suggested, and widely promoted, that the average cost to develop a new drug treatment is $2.6 billion. This is, especially for cutting-edge treatments, a reasonable estimate. For other treatments that are less complicated, the cost, of course would be less. Other challenges to this figure include “unrestricted grants” from pharmaceutical companies made to Tufts, which could be a potential source of bias, and the interest rate that Tufts CSDD uses for these estimates — which, if substituted by a more reasonable (common) value for capital investments, might lead this value to be more like $1.5 billion. Even at a range that would keep renowned statistician John Tukey happy, of, let’s say “$1.5 billion plus or minus $1 billion,” it’s still a tremendous investment that startups and established companies are making to bring new treatments from discovery through development hurdles, through clinical trials, and to the market.

John Tukey, the progenitor of the box-and-whisker plot (in 1970) would be proud, not only of the boxplot, but also because he'd “rather be approximately right than precisely wrong.”

As the saying goes, the first pill might cost $1 billion, but the next one costs 10 cents. This is certainly an oversimplification, but as a shorthand it’s important to realize that the companies that are endeavoring to produce these innovative treatments are absorbing a tremendous amount of risk, sometimes to their very existence. So, we have a complicated situation of producers, cost of innovation, social and public expectation, and availability.

At the same time, at the behest of Congress, an inter-agency Drug Shortage Task Force, led by the FDA, recently published (Q4 2019) the Drug Shortages: Root Causes and Potential Solutions report. The very first root causes listed in the report are “economic forces.” This is not surprising, as the Task Force included input from economists. But by being listed first, economic forces have undoubted primacy in the Task Force’s overall assumption as to their influence on drug shortages.

Additionally, three other root causes for drug shortages described by the Task Force are:

- Lack of incentives for manufacturers to produce less-profitable drugs

- The market does not recognize and reward manufacturers for “mature quality systems” that focus on continuous improvement and early detection of supply chain issues

- Logistical and regulatory challenges make it difficult for the market to recover from a disruption

I have been on several governmental and NGO panels discussing and establishing prices for drugs and medical devices, and more and more discussions recently have focused squarely on the availability of medical treatments, but there is often a tendency to forget how complicated pricing is, as well as the relationship of availability in predictive (forecastable) economic models.

We can’t talk about incentives for manufacturers until we ask ourselves the objective question, “What should the effectiveness of a medical treatment be worth?”

What Is The Price Of Efficacy?

There have been millions of complaints regarding the prices of therapies. Sovaldi, the hepatitis C oral treatment, which was in the news NOT because it has almost complete resolution of hepatitis C, the current treatment for which (decades on) is a liver transplant. Instead, Sovaldi was demonized in the media for its $1,000 per-pill cost (equating to about $84,000 for a full-course treatment).

Now, advanced treatments have allowed us to revisit disease states for which existing treatments have been inadequate (such as non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma). If they do work, as in the case of CAR-T therapies (mentioned above), what is the right price for efficacy?

If we look at what happens within markets with respect to incentives for spending on R&D, manufacturing, advertising, and consumer buying behavior, much of the picture is captured by comparing the spend on R&D activities with that for sales and marketing/advertising. Eight of the top 10 pharma companies spend more on advertising than they do on R&D activities. This is often touted as an overt negative by most media outlets, but be careful: Pharmaceuticals, like any other for-profit industry, function within capitalist economic structures, and it is their job to produce safe and effective medical treatments and return value to shareholders. Remember, people don’t flock to Instagram to fawn over the latest drug therapies as they do with designer handbags and sunglasses. So, to recover revenue from lengthy and expensive development cycles, pushing expensive advertisement campaigns largely makes sense.

Are There Really Drug Shortages?

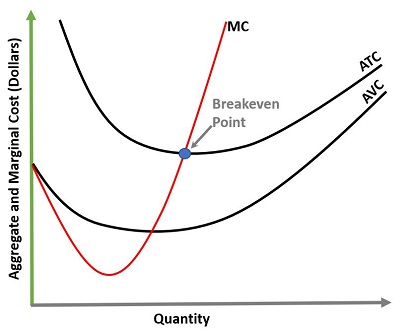

First, a short primer on econometrics: To determine if and where shortages exist requires looking at the difference between supply and demand. In economics, the principle we use is demand elasticity, whereby the supply and demand are inextricably linked with the variable of price. If something costs too much, this typically will tend to cause the demand curve to plunge. The manufacturer (or vendor), then, would have the choice of either facing reduced demand for the product (or service) or reducing the price in order to sell more units. Somewhere along this curve exists the breakeven point, where the price is set at an equilibrium point at which the total units sold multiplied by the price of each unit (revenue) is equal to the cost of production. This is where profit equals zero. The interesting thing about this point is it’s also the point of no future viability (or, “infinite altruism”). What this means is that a company that is producing and selling at a level at which there is no net profit cannot grow or further develop anything new.

Marginal and short-run analyses form the basis of allowing us to identify where it is profitable to expand operations or contract operations. MC=Marginal Cost (of producing additional units), ATC=Average Total Cost, and AVC=Average Variable Cost. The breakeven point represents where the cost to produce one additional unit has an identical value as the revenue generated from it (i.e., profit=0). Ideally, a business would like to spread their fixed costs over as many units as possible.

This is a common extant cause for the lack of innovation that generally exists in the world of vaccines. There are very few vaccines that return a considerable profit to their manufacturers. In fact, the most recent estimates for per-unit profit on influenza vaccines is $4. And remember, these are produced at very high quantities, so the production has harnessed a lot of economies of scale. Should they be more novel vaccines, or produced in a smaller quantity in a less efficient way, the per-unit revenue would be much less. So, there are therefore, relatively speaking, very few innovations within the vaccine side of the industry. Novel antigens, novel adjuvants, infrastructural changes to cell culture vaccines (from egg-based production, for example), and developmental changes for newer antigen targets and approaches all take a lot of time and money. And none, by their very nature, come for free. As an example, there has been great interest in a “universal” flu vaccine for a few decades — and the technology exists to be able to trial several different approaches (including, for example, targeting nuclear proteins or “stalk” chimeric hemagglutinin of the influenzaviridae). The joke within the immunization field is that the universal flu vaccine is coming in five to 10 years — a line that has been repeated for three decades. So each year, five to 10 years away represents a moving boundary of non-innovation. If we want more novel and more effective vaccines, we need to increase the overall capital that exists within the field. Translation: higher margins on vaccines sold.

What Drug Shortage?

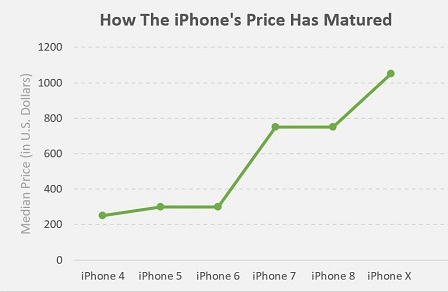

Now, back to the shortage “problem”: From a pure economics standpoint, a shortage only exists if producers are not sensitive to demand elasticity (re-read the section above if this concept is not clear). If something is selling out (i.e., available units becomes zero), this is either a production problem, a cost problem (not charging enough for each unit), or BOTH. So, to let a free market function properly, unfettered, would be to charge according to demand — so if a particular therapy is continuously at risk of selling out, then its offer price isn’t high enough. But then there’s the unavoidable variable of the social contract. If a particular product or service is perceived to be altruistic in nature, then there is a proportion of society that believes the product or service should be heavily subsidized up to and including a level of “free” (i.e., zero cost to the consumer). Consider, for example, the pricing trend of iPhones over the past several generations of the product:

Data source: Apple, Statista

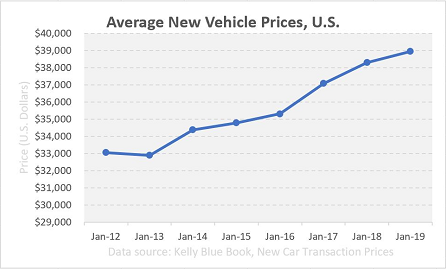

And similarly, here is a pricing trend of new cars over the past several years:

Data source: Kelly Blue Book, New Car Transaction Prices

Demand for iPhones and passenger vehicles can be modeled and controlled very precisely with cost. However, the argument goes, neither iPhones nor vehicles are the same as medical therapies, because a person’s health could be at risk, and the nature of the medical therapy is to assist in the process of healthcare. This is said to mean that the other types of products are “discretionary.”

But what about if a person needed to make an emergency call to avoid death to themselves or a bystander due to an accident or cardiac arrest? Or a person who couldn’t afford a vehicle opted to walk to work or to the store and, for lack of a vehicle, died of exposure (hypothermia)? These are both indirect causes of not having available a suitable risk insulation, and could, in this thought experiment, lead to morbidity or mortality. For more on this, check out philosophical treatments of The Heinz Dilemma and The Trolley Problem. Report back in the comments below with what you think.

Both of these examples, by the way, have occurred and give gravitas to the argument about the fuzzy boundaries and slippery slopes of the principles of morality and ethics. There is a lot of sociopolitical pressure, at any rate, to not let free market economics run without interference as far as healthcare treatments are concerned. It’s not so surprising that our models of drug costs and production have been so messy, for they were built to include the already-existing complicating variables of heavy government tampering, insurers, payers, and international trade organizations. So, we’re trying to piece the totality of the story together post hoc, rather than having prevented the issues in the first place.

The FDA’s Report And The Future of Shortages

One of the subtle features within the FDA’s report on drug shortages is the contention that a long-view look at manufacturability and quality will change market dynamics and lead to fewer shortage and stockout situations.

The tricky part with this is how behavioral economics functions in the context of predicting future behavior and loss aversion. Our estimates of the future — and of our future selves — are always overly optimistic under measured constraints, and they defy, behaviorally, the typical models of economics (and are fundamentally why behavioral economics itself became a field of its own). Imagining that the future will be much better in all contexts, and that batch failures and shortages will naturally reduce, is a fantasy. We can work for these effects to happen, but they don’t happen spontaneously on their own. And frankly, they occur on an as-needed basis, following Einstein’s principle (paraphrased) of “the significant problems we face cannot be solved with the same level of thinking we were at when we created them.” So as the industry advances, our problem-solving paths and solutions for previous-generation problems aren’t identical to those we need for the upcoming ones. Such is the case for manufacturing problems encountered in cell therapies, for example, which have led to adverse market reactions to several manufacturers, including bluebird bio.

Market forces and consumerism aren’t always so interested in the future-looking prospect of reliability. Something that’s likely to be better at an arbitrary time point in the future doesn’t often capture the interest of consumers when compared to something that’s available on a timescale of “now.”

Emotion trumps evidence and logic. It should be self-evident which machine to buy (the one that's got high reliability), but the sales figures unmask a great truth deeply hidden: Logic doesn't necessarily apply in emotional decision-making.

This matters because one of the FDA’s recommendations to address future shortages is a long-term view of improved quality in manufacturing processes (see second bullet below). It is patently true that improvements to processes can facilitate economies of scale, reduce defects and batch failures, and lead in a variety of ways to more widely available and less costly medical treatments. But this is a much more deliberative, slower, methodical approach to getting there.

Additional recommendations from the Task Force include:

- Creating a shared understanding of the impact of drug shortages on patients and the contracting practices that may contribute to shortages

- Developing a rating system to incentivize drug manufacturers to invest in quality management maturity for their facilities

- Promoting sustainable private sector contracts (e.g., with payers, purchasers, and group purchasing organizations) to make sure there is a reliable supply of medically important drugs.

The above list undoubtedly, in totality, would lead to the opportunity to reduce shortages. But the items above are also more qualitative, fragile, and reliant on concepts such as awareness, training, and ratings, as well as promotion.

The drug shortage report also describes legislative proposals in the president’s FY2020 budget and planned FDA initiatives to prevent and mitigate drug shortages that look at improved data sharing, risk management, lengthened expiration dates for drugs, and internationally harmonized guidelines for a pharmaceutical quality system. While some of these can help offset costs and prevent the incursion of costs, they also suffer from the philosophical difficulty of operational excellence and quality improvement campaigns, proving the avoidance of costs that you never incurred is enormously difficult. And while I always say, “Prevention beats correction 100 percent of the time,” designing systems properly (using, for example, lean, Six Sigma, QbD, PAT, etc.) involves a lot of up-front costs, and that’s perceived as financial risk to many organizations. And while the FDA and the Task Force stated explicitly in the report that such organizational improvements should be incentivized, this is not synonymous with “such organizational improvements shall be incentivized.” Finding this feedback loop between sponsor companies and regulatory agencies is a difficult thing, and it is not an immediate financial incentive. Long-term incentives can be great, but they don’t function linearly in a psychological sense as an immediate incentive. Would you want a $50 bonus tomorrow as a behavioral incentive, or the possibility of $1,000 next year? The research literature is very clear that, for the most part, the former is much (much) more preferable than the latter. We aren’t, as an industry putting these principles into best practice as well as we could/should.

Rome Burned, And Nero Played The Fiddle

The divide between the pharma industry and the public is very real and more vociferous than ever in history. Even amidst some of the historical problems that led to the formation of various divisions in the FDA, and the FDA itself, public discord wasn’t higher than it is now. If you haven’t availed yourself of the vitriol on social media about Big Pharma, perhaps you should calibrate yourself by checking out the prevailing wisdom of the “average” social media participant about Big Pharma, drugs, and drug prices. Or maybe if you haven’t yet, don’t. Some people find that being oblivious is a much less stressful way to live. Nero playing his fiddle while Rome burned in July 64 AD (while not exactly historically accurate) could serve as a metaphor for our current industry situation: 1956 years later, we as an industry can either be the architects of our own undoing and downfall, or we can learn from data — which we all claim to do all the time — and correct our behavior and approaches.

Rome burned, and Nero played the fiddle. Ask yourself: "Are we architects of our own undoing and downfall, whilst thinking we're doing great? Or do we learn from data and public discourse?" (Artwork courtesy of author)

Jokes aside, there is a huge gulf between what the consumers and manufacturers of medical treatments think. But just trumpeting clinical and cold dollar figures and efficacy data (which the public doesn’t understand) as “facts,” and not being sensitive to how our industry’s products are viewed by the public and used to prolong or preserve life, is to miss a huge opportunity in the overall conversation of what matters to people. Similarly, as in the world of behavioral neuroscience, the content of a spoken conversation is often gauged as less important to listeners than the nonverbal communication cues. We can’t (and shouldn’t) ignore the 90 percent of the conversation with the global pharma market that matters, and that involves the public’s reaction and emotional concerns, including regarding availability and price. Even if models suggest that it’s not rational, we owe it to humanity.

About The Author:

Ben Locwin, PhD, MBA, MS, MBB, is a healthcare executive who has worked with regulatory authorities and organizations to bring the future of better Quality within reach. This work has transcended industries and has included work improving the quality of patient care in hospitals and emergent and clinical care centers, and improving quality in the aerospace, automotive, food and beverage, and energy sectors. Connect with him on LinkedIn and/or Twitter.

Ben Locwin, PhD, MBA, MS, MBB, is a healthcare executive who has worked with regulatory authorities and organizations to bring the future of better Quality within reach. This work has transcended industries and has included work improving the quality of patient care in hospitals and emergent and clinical care centers, and improving quality in the aerospace, automotive, food and beverage, and energy sectors. Connect with him on LinkedIn and/or Twitter.