Facilitating Data Integrity Through Risk-Based Confirmation Of Performance

By James Vesper, Ph.D., MPH, ValSource, LLC

A different way to think about verify, review, and check

If you are flying on a commercial airline, it is common to hear a flight attendant say, “Arm doors and cross-check,” with a response from other flight crew members of, “One-L, One-R.” Or when pilots are getting instructions from the air traffic controller, they will repeat the instruction to ensure they heard it correctly. And most of us, before leaving our homes for a trip, will double-check to see that we have wallets, keys, mobile phones, passports, tickets, and anything else that is particularly important. In each of these examples, people want a level of confidence that things were done and done correctly.

response from other flight crew members of, “One-L, One-R.” Or when pilots are getting instructions from the air traffic controller, they will repeat the instruction to ensure they heard it correctly. And most of us, before leaving our homes for a trip, will double-check to see that we have wallets, keys, mobile phones, passports, tickets, and anything else that is particularly important. In each of these examples, people want a level of confidence that things were done and done correctly.

In a similar way, we in pharma and biopharma are required to verify or check or double-check an action or event to be sure it was performed and performed correctly. But what do these words really mean? How do they differ in terms of their actual execution?

These questions came as the result of my looking at the batch production records of a relatively new drug manufacturing firm. Each and every step had two columns associated with the instruction: one column required the initials of the technician that performed the step; the other had a place for the verifier to initial. In other words, every step needed both a performer and a verifier.

In observing the technicians as they filled out the document, it was apparent that they were not witnessing in real time each step or sub-step. Rather, they were doing a perfunctory signing of the forms; there was little independent confirmation. When the technicians were asked what “verification” meant to them, there was a variety of responses. Very few people said anything about “real-time witnessing” or redoing the step.

What Do GMPs Say?

If one looks at the drug GMP regulations, requirements, and guidances from different countries and regions, health authorities in the U.S., Canada, U.K., EU, and PIC/S do not give definitions of these terms in their GMPs. What is common in the words — check, review, verify — is that health authorities want there to be a confirmation that something is done and has been done correctly. Two key questions are then: (1) what do these words each mean? and (2) if they mean different things, how are they to be applied? Could risk-based thinking help us understand their use?

For much of industry, verify or verification is something done in real time. Witness is often a synonym — you are watching someone perform a critical activity to ensure that it was done and done correctly. Review or check are terms that, as used in pharma/biopharma, are legitimately done after the fact; they do not need to be performed in real time.

Why is this so important? A big reason is the emphasis on data integrity. Reviewing, checking, and verifying information help ensure the data is reliable and trustworthy, a requirement found in U.S. 21 CFR 111 — the regulation that covers electronic documents and electronic signatures but that also has elements like this that can be conceptually applied to paper-based documents as well. Other characteristics of a well-prepared document are arranged as an acronym known as ALCOA Plus (attributable, legible, contemporaneous, original, accurate, complete, consistent, enduring, and available).2

Defining Key Terms

Since there are no “official” definitions that can be found in the GMP requirements of the U.S., Canada, and EU, we can look to industry practice and see how it puts these words into use.

|

Term |

Typical industry definition |

Example |

|

Verify |

Having real-time witness of an event. |

Adding materials (“charging”) to a blender.

|

|

|

This sometimes involves a second person repeating the same activity with the hope that the same result will be achieved.

|

Performing a line clearance on a packaging/labeling line. |

|

Double-check |

This sometimes involves a second person repeating the same activity with the hope that the same result will be achieved.

|

Recalculating a result, for example, a reconciliation. |

|

Review |

Having a second person examine something (usually a document), generally for adherence to certain requirements. Often, a word or two follows the requirement for “review.”

|

Reviewing a procedure for technical accuracy prior to approval. |

|

Check |

Examining something to ensure it meets requirements or is correct. Often used interchangeably with review. Best practice is to provide some guidance for what is required. Often a word or two follows the requirement for “review.”

|

Checking filter assembly to confirm it was properly set up and installed; checking a printout of a validated, automated system (e.g., autoclave) to assure that it operated as intended. |

What is common to all these actions is that they confirm that something is correct, that it meets the specifications or requirements, or that the proper action was taken.

Use Of Risk-based Thinking

If one were to arrange these and several other terms related to confirmation along a spectrum based on risk, how would they be positioned? And is that something that is even advisable?

The ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management (QRM) document adopted by the FDA and most other health authorities provides examples in its Annex II on how QRM can be used. The first topic is Documentation, with this suggested use: “To review current interpretations and application of regulatory expectations.”3 Additionally, a Technical Report from the World Health Organization states, “Data collection and recording. All data collection and recording should be performed following GDRP and should apply risk-based controls to protect and verify critical data.”4 One could say, when looking at this another way, if some data is considered critical, other data is not.

The approach that is proposed here is not dissimilar to the FDA’s approach to process validation. In its guideline, the FDA requires qualification and validation to provide “a high degree of assurance,” which is obtained through “objective information and data.”5 The guideline incorporates a risk-based approach: “The degree of control… should be commensurate with their risk to the process and process output.” What we are doing through confirmation is providing a high degree of assurance through a variety of different, situation-appropriate actions.

The source that provides the most detail about verification and review in terms of the criticality of the data is a draft document from the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme or PIC/S that, in a guidance to health authority inspectors says:6

When and who should verify the records?

A – Records of critical process steps, e.g., critical steps within batch records, should be:

- reviewed/witnessed by designated personnel (e.g., production supervisor) at the time of operations occurring; and

- reviewed by an authorized person within the production department before sending them to the quality assurance unit; and

- reviewed and approved by the quality assurance unit (e.g., authorized person/qualified person) before release or distribution of the batch produced.

B – Batch production records of non-critical process steps are generally reviewed by production personnel according to an approved procedure.

C – Laboratory records for testing steps should also be reviewed by designated personnel (e.g., second analysts) following completion of testing. Reviewers are expected to check all entries and critical calculations and undertake appropriate assessment of the veracity of test results in accordance with data integrity principles.

This verification must be conducted after performing production-related tasks and activities.

This verification must be signed or initialed and dated by the appropriate persons.

Local SOPs must be in place to describe the process for review of written documents.

Considering Risk-based Confirmation

So, knowing that there is no clear GMP definition on what verification, review, and check mean and that some regulators distinguish between critical and non-critical entries in a record, how can we apply risk-based thinking to what is confirmation? Or, in other words, what level of confidence do you really need that an action or event occurred or that the recorded data is accurate? If everything is held to the same high standard, meaning that everything is important, then, in fact, nothing is important.

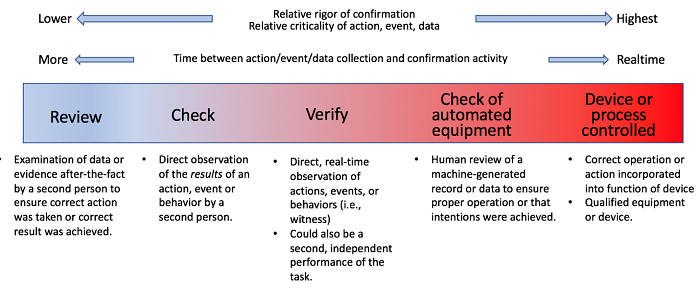

The following approach is proposed to show the ways that “confirmation” can be achieved. Figure 1 presents this as a graphic.

|

Term |

Proposed definition |

Example |

|

Device or process controlled |

|

|

|

Check of automated equipment |

|

|

|

Verify |

|

|

|

Check |

|

|

|

Review |

|

|

Figure 1: The spectrum of confirmation

As one moves down the list from the device or process-controlled confirmation to review, the rigor decreases and there is more time between the event that is being confirmed (and, in a sense, controlled) and the confirmation performed. There is also an increased risk to operators (e.g., safety and health), products, and patients if the event is not executed fully and properly.

Benefits Of This Approach

Looking at confirmation as a category allows us to use a risk-based approach and have a spectrum of activity and risk-appropriate actions that we can take.

Are we just playing with words here? We know that language can drive and support behavior. With the global interest in data and information that is accurate, reliable, and trustworthy, health authorities want to have confidence that entries are what they are represented to be. Having specific definitions — that are risk-based — for several different forms of confirmation can communicate what exactly is to be done, help standardize performance, and support efforts for data integrity.

References:

- US FDA. (2018). Electronic Records; Electronic Signatures (regulation). Silver Springs, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm Part 11

- Rattan, A.K. (2017). What is Data Integrity? PDA J Pharm Sci Technol., pii: pdajpst.2017.007765. doi: 10.5731/pdajpst.2017.007765.

- ICH. (2005). Q9 – Quality Risk Management. Geneva: International Conference on Harmonization. https://www.ich.org/products/guidelines/quality/article/quality-guidelines.html

- WHO. (2011). Guidance on Good Data and Record Management Practices. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 996, Annex . Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/quality_assurance/Guidance-on-good-data-management-practices_QAS15-624_16092015.pdf

- US FDA. (2011). Process Validation: General Principles and Practices – Guidance for Industry. Silver Springs, MD: U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/process-validation-general-principles-and-practices

- PIC/S. (2016). Good Practices for Data Management and Integrity in Regulated GMP/GDP Environments. Geneva: Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme. https://www.picscheme.org/en/publications

About The Author:

James Vesper is director of ValSource Learning Solutions and has more than 35 years of experience in the pharmaceutical industry. He worked at Eli Lilly and Company before establishing the consulting firm LearningPlus. Vesper joined ValSource in 2017 and designs training courses and performance solutions. He has worked around the world at pharma and biopharma firms, trained inspectors from a number of health authorities, and written five books. Vesper received his Ph.D. in education from Murdoch University (Perth, Western Australia) and his master of public health degree from the University of Michigan School of Public Health (Ann Arbor). You can reach him at jvesper@valsource.com.

James Vesper is director of ValSource Learning Solutions and has more than 35 years of experience in the pharmaceutical industry. He worked at Eli Lilly and Company before establishing the consulting firm LearningPlus. Vesper joined ValSource in 2017 and designs training courses and performance solutions. He has worked around the world at pharma and biopharma firms, trained inspectors from a number of health authorities, and written five books. Vesper received his Ph.D. in education from Murdoch University (Perth, Western Australia) and his master of public health degree from the University of Michigan School of Public Health (Ann Arbor). You can reach him at jvesper@valsource.com.