Applying The Johari Window To Manage Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Risk

By James Morris, executive director, Pharmaceutical Services, NSF International

The recalls of generic versions of the drug valsartan and related products losartan and irbesartan (ARB class products, or angiotension receptor blockers to treat high blood pressure) due to high levels of nitrosamine impurities have once again put the spotlight on sourcing strategies and the globalization of the pharmaceutical supply chain.

or angiotension receptor blockers to treat high blood pressure) due to high levels of nitrosamine impurities have once again put the spotlight on sourcing strategies and the globalization of the pharmaceutical supply chain.

Background

Historically, vertically integrated pharmaceutical companies formulated drug products with active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) they produced themselves. Today, the vast majority of APIs are sourced from India and China and, while GMP compliance in these locations continues to improve, there will always be a knowledge gap between the innovator of a drug and the generic producer(s) of the same drug product. Furthermore, all manufacturers are under pressure to reduce costs — all the more so when profit margins are as tight as they are for the generic drug manufacturer.

Finding The Cause

The producers of the ARB drug subtance were undoubtedly trying find cost savings and, in so doing, failed to fully evaluate the impact of an alternative synthesis route and impurities in certain solvents and reagents used to manufacture the drug substance. This was compounded by the fact that the impurities were not expected and, therefore, tests were not performed that would have detected the impurities. And while the response by industry and regulators across the globe has been significant — extensive product recalls, new analytical methods, regulatory guidance, broad based communication of the risks to the public — the response must also consider actions that will preclude reccurence of a similar, avoidable issue.

The key players involved in managing this ARB issue, regulators and industry, will have asked questions about the supply chains and the supply organizations. These questions will have included:

- How were these production changes managed?

- Were process scientists, development chemists, and other experts consulted?

- How could these impurities have gone undetected?

- Was there advance notification of the planned planned changes to the API production process?

- Could the supplier audit program have identified the risk?

The Answers

First, there is no substitute for product and process knowledge. This incident did not happen to the innovator of the drug substance — it happened to a subset of the generic manufacturers licensed to manufacture the drug substance and the respective drug products.

It is not just what the manufacturer knows of their products and processes that counts, it is also what they should have known or anticipated. Nitrosamines present known risks and their formation is expected under certain conditions. With the benefit of hindsight, perhaps these conditions are better appreciated, but the role of change control in the pharmaceutical industry is to thoroughly evaluate changes in advance of implementation.

Therefore, the second answer lies with a robust change control process. A distinguishing characteristic of great companies is that they excel at managing changes. Top-tier companies will manage product and process changes with kid gloves. Changes will be triaged on the basis of risk, and proper studies will be conducted when they may not have sufficient knowledge of the potential product impact. I have worked with many pharmaceutical companies that will bring on external experts to properly evaluate a manufacturing change and cover all angles before agreeing to move ahead. That should be the norm when the underlying patient safety risk of a change is considered to be high.

Third, a component of change management is risk assessment. Quality risk management is well embedded in most pharma companies, but in some cases it is an exercise in justifying a change rather than a tool to establish known risks and identify mitigating actions. In this case, the presence of sodium nitrate, together with secondary or tertiary amines within the same process step or the use of recovered solvents or use of solvents processed by third parties, should have signaled risk factors warranting mitigating action. Such action would have included suitable analytical methods to detect possible impurities in the process. Companies need to determine whether their risk management procedures are serving their intended purpose. This can be achieved through internal audit or third-party reviews of risk assesment methodologies, risk reduction actions, and their associated risk registers.

Quality systems such as change control, investigations, and notification to management must be in place. But like all quality systems, these are managed by people and are only as good as the people involved in the decision-making process. This brings us to a fourth key characteristic, which is the quality mind-set at manufacturing sites. I would argue that while there are excellent technical professionals in companies throughout India and China, their ability to push back and challenge when data does not support a change is inherently weak. The hierarchical structure and cultural norms in these locations often do not foster the openness that characterizes an environment where questions are raised and risks are properly vetted. But this is not a geographical issue; all pharma companies must work extremely hard to foster a work environment that puts a hold on product where the underlying data does not support a change or product release decision. They must work even harder to ensure an investigation process is free of bias and science drives the investigation, not expediency. When a process scientist identifies an opportunity to increase yield, alter the synthesis route, or reuse process solvents, a red flag should go up to challenge and throughly evaluate the change. The quality-minded work environment is fostered by the senior leader who sets the expectation that product quality and patient safety are more important than meeting a project timeline.

Finally, external or third-party audit programs must be best in class. Granted, quality audits are merely a sampling exercise, and it would have taken an astute auditor with excellent understanding of drug substance manufacturing and solvent recovery risks to have recognized the ARB issue before it surfaced in the marketplace. However, a thorough audit program would have ensured the technical agreements and change notification systems were functioning properly.

The Regulatory Requirements

The answer to the question of whether the regulatory requirements were sufficient and, if followed, would have prevented this problem is a qualified yes. This answer is based on the following:

ICH Q7 and Eudralex Volume 4 Part 2, section 11.21 requires: An impurity profile describing the identified and unidentified impurities present in a typical batch produced by a specific controlled production process should normally be established for each API. The impurity profile should include the identity or some qualitative analytical designation (e.g., retention time), the range of each impurity observed, and classification of each identified impurity (e.g., inorganic, organic, solvent).

The opportunity to establish an impurity profile for a drug sustance manufacturing change is during the development and evaluation of that change. Once the change is approved, companies move forward, and it would have taken a new change and perhaps a new analytical method to recognize that the impurity profile of the drug substance had shifted. Again, this takes us back to the robustness of the change control system and the rigor of the evaluation carried out by the drug substance manufacturer(s).

Responsibilities

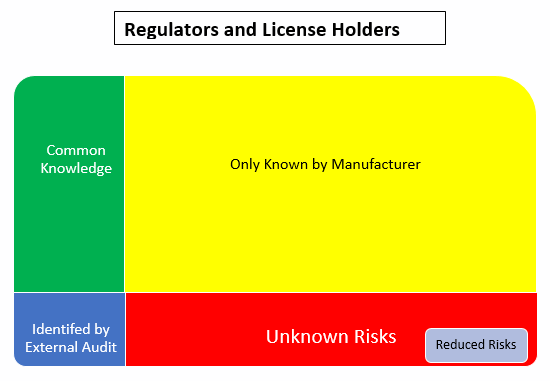

The answers and the resolution of the contributing factors to this problem are complex, involving multiple organizations and processes. A framework that illustrates the management of knowledge from an external audit point of view is the Johari Window. Although it was originally developed to improve mutual understanding between individuals within a group, the Johari Window can also be used as a technique that improves understanding and the relationship between processes and organizations.

Using the Johari Window model, the:

- Green box is the common knowledge shared between the involved parties

- Yellow box is known only to the manufacturer/supplier

- Blue box is what the external audits and inspections have been able to identify

- Red box is the unknown risks. Nobody knows about these so they are unmitigated

- Grey box is the result of reduced risks that comes from communication/sharing between the involved parties to identify and mitigate the unknown risks

The Johari Window model helps us recognize that there is always going to be an element of surprise (the red box). These are the things we don’t know about and unfortunately learn about after implementation. In summary, the way to prevent a similar issue is to follow these basic principles, ultimately reducing the size of the red box or the unknown risks:

- Maximize product/process knowledge and understanding. ICH Q10 Pharmaceutical Quality Systems guidance emphasizes the importance of knowledge management. Companies must be proactive in this area and identify systems that maximize and retain product/process knowledge.

- Ensure investigation and change control systems are robust and involve subject matter experts, people who can thoroughly evaluate product and process changes.

- Robust effectiveness checks after the implementation of a change should confirm whether there may have been unintended consequences of the change.

- Ensure that risk assessments are not “paper exercises” but are truly adding value to the organization. Routinely monitor risk management processes through internal audit of these systems.

- Develop a quality mind-set and foster a culture where concerns and questions raised by technical personnel are respected and properly evaluated for their scientific merit. Where there are concerns about the quality mind-set or culture at a site, assessments and action plans must be put in place to embed a quality-/patient-focused decision paradigm.

- Ensure supplier audit programs confirm that quality agreements require advance customer notification of significant changes and such notifications are thoroughly evaluated before approval to implement such change is granted.

- Ensure those points in the supply chain that represent the greatest product quality risk are audited by well-qualified auditors, versed in the technology, or identify third-party organizations that can provide that expertise.

When these principles are in place by manufacturers and their customers, the outcome is much tighter control and greatly increased confidence in the supply chain. Applying these basic principles will help minimize risk and shrink the size of the red zone or unknown risks inherent in any complex manufacturing supply chain.

Resources:

- European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines' (EDQM) response to nitrosamine contamination

- FDA's information about nitrosamine impurities in medications

- NSF's nitrosamine risk exposure self-assessment questionnaire (PDF)

- NSF Webinar: Nitrosamines in Medicinal Products – Assessing the Risks

About The Author:

Jim Morris has over 25 years of pharmaceutical management experience in both plant operations and corporate offices in the U.S. and Europe. He has held positions as deputy director of QA/QC and regulatory affairs at Mass Biologics, director of QA/QC for the Biologics business unit of Cilag AG, and a number of quality assurance and manufacturing roles with Pfizer over a 16-year time frame, culminating as the head of quality assurance in Latina, Italy. His areas of recognized expertise include: quality leadership development, supply chain auditing and managing audit programs, quality management systems parenteral product manufacture and compliance, and OTC product manufacture and compliance.

Jim Morris has over 25 years of pharmaceutical management experience in both plant operations and corporate offices in the U.S. and Europe. He has held positions as deputy director of QA/QC and regulatory affairs at Mass Biologics, director of QA/QC for the Biologics business unit of Cilag AG, and a number of quality assurance and manufacturing roles with Pfizer over a 16-year time frame, culminating as the head of quality assurance in Latina, Italy. His areas of recognized expertise include: quality leadership development, supply chain auditing and managing audit programs, quality management systems parenteral product manufacture and compliance, and OTC product manufacture and compliance.