Analyzing 2017 FDA Warning Letters Citing Process Validation, Supplier Controls, & OTC Manufacture

By Barbara Unger, Unger Consulting Inc.

Shortcomings in data governance and data integrity are a prominent feature in drug GMP warning letters over the past three years. FDA inspections also focused on contracted services including contract manufacture and contract laboratories. Additional areas were the subject of FDA investigator attention in CY2017 but may have been overshadowed by these two. We address them here, and they include:

Shortcomings in data governance and data integrity are a prominent feature in drug GMP warning letters over the past three years. FDA inspections also focused on contracted services including contract manufacture and contract laboratories. Additional areas were the subject of FDA investigator attention in CY2017 but may have been overshadowed by these two. We address them here, and they include:

- Focus on failures in process validation, with an emphasis on failure to conduct ongoing process monitoring to ensure the process remains under control

- Focus on supplier controls, including testing of incoming raw materials and components including APIs and

- Increased, and seemingly disproportionate, focus on over-the-counter (OTC) drug product manufacturers, both foreign and domestic, including manufacturers of homeopathic products.

Each represents the FDA’s enforcement of fundamental GMP requirements rather than a novel interpretation or implementation of a new requirement. We address them in turn below.

Process Validation

The FDA continues to cite producers of sterile drug products for failing to validate aseptic processes and sterilization processes as required by 21 CFR 211.113(b). Now, however, we see an increasing group of firms manufacturing non-sterile products that appear to skip the process validation concept entirely. Moreover, those firms do not have an ongoing program to ensure that the process remained in a state of control. The latter appears to be the point of emphasis in recent warning letters. Common boilerplate text found in these warning letters includes: “You have not validated the processes used to manufacture your drug products. You did not perform process performance qualification studies, and lacked an ongoing program for monitoring process control to ensure stable manufacturing operations and consistent drug quality.”

The FDA also appears to link manufacturing failures and repeated out-of-specification (OOS) events to a failure to understand and design an adequate manufacturing process and controls. Note that what the FDA expects is consistent with its 2011 Guidance for Industry, Process Validation: General Principles and Practices, which states “Focusing exclusively on qualification efforts without also understanding the manufacturing process and associated variations may not lead to adequate assurance of quality.” Rather, firms should:

- “Understand the sources of variation

- Detect the presence and degree of variation

- Understand the impact of variation on the process and ultimately on product attributes

- Control the variation in a manner commensurate with the risk it represents to the process and product.”

The following examples include highlights of some of the critical text that reflects the requirements in the FDA guidance.

- Warning Letter 320-17-46 issued on Aug. 15, 2017 states “Your firm does not have an adequate ongoing program for monitoring process control to ensure stable manufacturing operations and consistent drug quality.” The deficiency identifies that “Your investigations into process deviations and out-of-specification (OOS) laboratory results are insufficient, and do not include scientifically-supported conclusions.” In response to the warning letter, the firm is to provide information to the FDA including “Your detailed retrospective review of the manufacturing process validation for each product that can be exported to the U.S., including (b)(4), to ensure your manufacturing processes are capable of consistently yielding finished products that meet quality attributes and manufacturing requirements. For each process, identify sources of variability in your raw materials and manufacturing process, and indicate the steps you have implemented to reduce variability or mitigate its potential effects on the quality of your products.”

- Warning Letter 320-18-06 issued Nov. 6, 2017 addresses, among other issues, lack of established adequate hold times for bulk product. The firm invalidated OOSs without adequate investigations or identification of root cause and remediation. The FDA asked the firm to provide the following in response to the warning letter:

- “Perform a retrospective review of all batches shipped to the U.S. Place batches with (b)(4) held more than (b)(4) on the stability program. Provide initial test results (dissolution, content uniformity, and assay) on each such batch within 45 days of receipt of this letter.

- For each batch with an OOS result (whether or not it was later invalidated) since 2014, provide the associated holding times for each significant manufacturing step.

- For each product, perform representative and robust studies to establish appropriate time limits for all significant manufacturing steps.

- Create improved production procedures that prevent future occurrences of unnecessarily long hold times.

- Provide interim procedures that establish in-process hold time restrictions.”

- Warning Letter 320-18-12 issued Dec. 4, 2017 included inadequate management of OOS results. The FDA asks the firm to “For any OOS with an inconclusive or no root cause identified in the laboratory, include a thorough review of production (e.g., batch manufacturing records, adequacy of manufacturing steps, raw materials, process capability, deviation history, batch failure history). Provide a CAPA plan that identifies the potential manufacturing root causes for each such investigation and includes process improvements where appropriate.”

Thus, the FDA potentially associates OOS events without an assignable cause to manufacturing processes that may not be adequately controlled or understood. The two activities should feed into an adequate validation protocol and ongoing process controls.

The FDA places significant emphasis on understanding the manufacturing process and factors that contribute to variability to ensure a robust process validation exercise. Failures in these areas are suggested by an unexpected number of OOS events for which root cause cannot be determined, as well as an unexpected number of lot rejections.

Supplier Controls

The reported economic adulteration of heparin in 2008 placed focus on the importance of supply chain controls. We continue to see FDA enforcement focus in this area, which represents a fundamental part of GMPs, and warning letters in 2017 identified many instances where firms were out of compliance with the relevant fundamentals. Looking forward to the 2018 warning letter roundup that we will do in early 2019, many of the warning letters issued this year to OTC manufacturers have deficiencies similar to the one cited in the third bullet point below. Firms should implement a risk-based program to ensure suppliers are adequately qualified based on the potential impact of the material or component on product quality and patient safety. 21 CFR 211.84(d)(1) requires that firms perform a minimum of an identity test on incoming raw materials. Firms may reduce other testing if they qualify suppliers by generally conducting an on-site audit and verification of results provided on the certificate of analysis (COA) for multiple lots, and then repeat this verification periodically. Another failure in supplier controls that has been documented at least several times is a misrepresentation of information in the COA, in which the supply chain is not transparent to the purchasing firm. The following are several examples:

- WL 320-17-35 issued April 20, 2017 addressed misrepresentation of the supply chain.

“You omitted the names and addresses of the original manufacturers of your API on certificates of analysis (COA) you issued to your customers. You generated your COA by replacing the original manufacturers’ information with your letterhead.

During our inspection, we found that two of your suppliers were not registered with the FDA as drug manufacturers at the time of inspection. However, you shipped API from these firms to the United and declared on importation documents and the COA that you provided to your customers that you were the manufacturer. Your failure to declare the original manufacturers on your importation documents and COA provided to your customers enabled the entry of unregistered firms’ products into the United States.

Customers and regulators rely on COA for information about the quality and source of drugs and their components. Omitting information from COA compromises supply-chain accountability and traceability, and may put consumers at risk.”

- WL 2017-DET-04 issued April 20, 2017 also addressed misrepresentation of the supply chain.

“You repeatedly omitted the name and address of the original API manufacturer on the certificates of analysis (COA) you issued to your customers and did not include a copy of the original batch certificate. Additionally, your firm did not conduct a secondary review of COA you generated to ensure the information presented to your customers was accurate.

Regulators and customers rely on the COA to provide accurate information about the quality and sourcing of drugs and their components. Omitting information on a COA compromises supply chain accountability and traceability, and may put consumers at risk.”

- WL 320-17-44 issued Aug. 2, 2017 addresses inadequate controls over raw materials and components regarding testing.

“You failed to test incoming active pharmaceutical ingredients and other components you use in manufacturing (b)(4) drug products to determine their identity, purity, strength, or other appropriate specifications.

Your response claimed that because it is not feasible for you to perform component identification testing, you would instead rely on your supplier’s certificate of analysis (COA) for the identity of each incoming component. Your response is inadequate for two reasons. First, you must conduct at least one specific identity test to analyze all incoming components. You may not rely on your supplier’s COA to verify the identity of your components. Your response was also inadequate because you did not indicate how you would address your failure to test all incoming components for specifications other than identity.”

OTC Manufacturing

Let’s begin this section with a focus on OTC manufacturers and how the FDA regulates them. Over the counter drugs that meet OTC monographs do not require approval prior to marketing, unlike those that must gain approval through the NDA/BLA/ANDA regulatory processes. OTC drug products that we are all most familiar with are generally oral dosage forms, creams, and ointments that we purchase at our local drug store. The GMPs for OTC drug products are the same as for prescription drugs in 21 CFR 211.

The FDA’s focus on OTC manufacturers is likely due to the large number of consumers who use these products, rather than any inherent risk their manufacturing processes pose to patient safety. While not at the risk level of manufacturers of sterile parenteral products, this group of manufacturers is significant for the breadth and depth of their reach in the U.S. population. Who among us doesn’t have a half dozen or more of these products in our medicine cabinets?

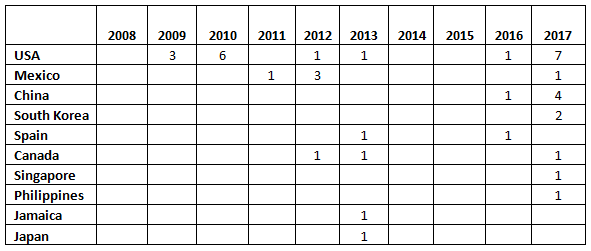

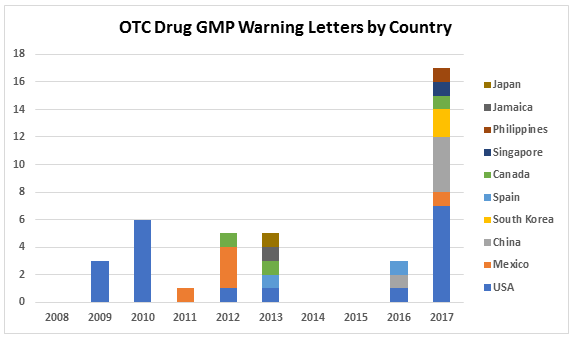

Table 1 and Figure 1 present the geographic distribution of OTC firms that received warning letters from 2008 to 2017. The most striking feature is that the initial geographic focus was on firms located in the U.S. Starting in 2011 and continuing through 2016, firms in a range of countries received one warning letter, with the exception of Mexico, which had three OTC firms that received warning letters in 2012. In 2013, five countries, including the U.S., were home to OTC sites that received warning letters. The explosion occurred in CY 2017, when a total of 17 warning letters were issued to OTC manufacturers in seven countries, including the U.S. The seven letters issued to firms in the U.S. topped the list. One each was issued to firms in Mexico and Canada. The Asia Pacific area, including China, South Singapore, and the Philippines accounted for a total of eight warning letters. China led this group with four sites and South Korea followed with two.

This trend is accelerating in CY2018, with 14 warning letters issued to OTC manufacturers posted on the FDA website effective April 18, 2018 out of a total of 33 drug GMP warning letters. It appears that the 2018 total will easily exceed that of 2017. This year, the focus so far appears to be on OTC manufacturers located outside the U.S., with a large focus on Asia Pacific countries. Look for this trend to continue; we will update this information in the FY2018 drug warning letter wrap-up at the end of this year. Many of the deficiencies identified at these firms are failures to address basic GMP requirements, including an inadequate quality unit, failure to validate manufacturing process, failure to test incoming raw materials and components and rather rely on the supplier’s COA, and failure to test all lots of product to ensure they meet specifications prior to their release to market. These warning letters do not include novel interpretation of GMP requirements, but rather address a failure to grasp and implement the basics of GMP.

Table 1: Geographic Distribution of Warning Letters to OTC Manufacturers

Figure 1: Geographic distribution of warning letters to OCT manufacturers

Conclusion

Lack of process validation, and particularly the failure to have an ongoing monitoring program to ensure the process remains in a state of control, is also notable. The expectation for an ongoing process control program reflects the requirements in the 2011 Guidance for Industry, Process Validation: General Principles and Practices. The FDA is enforcing the expectation that manufacturers understand the sources of variability in their processes, including that contributed by raw materials, and the expectation for ongoing process monitoring raised in the 2011 guidance.

The continued focus on fundamental deficiencies in supply chain controls is significant. The FDA several times identified firms that falsely misrepresent the origin of materials in the certificate of analysis provided to customers. Also, firms were not testing raw materials and components upon receipt but instead were relying on the COA values without verifying their trustworthiness. All of the shortcomings in these areas do not represent new requirements or new interpretations of existing requirements. Instead, they demonstrate a lack of understanding and application of essential GMP requirements.

The focus on OTC manufacturers is likely the most significant and is continuing at an increased rate in 2018. The FDA is likely focused on this product category based on the number of individuals who use these products on a daily basis. This may be approaching or replacing compounding pharmacies and outsourcing facilities as a product category that is subject to increased and highly visible enforcement.

I predict that the FDA will continue to identify and focus on deficiencies in process validation and supply chain controls, particularly within the OTC market segment. Data integrity and CMOs will also continue to be areas of challenge for pharmaceutical and API firms. We will evaluate all of this in the FY 2018 warning letter report that we intend to publish at the end of this calendar year.

About The Author:

Barbara Unger formed Unger Consulting, Inc. in December 2014 to provide GMP auditing and regulatory intelligence services to the pharmaceutical industry, including auditing and remediation in data management and data integrity. Her auditing experience includes leadership of the Amgen corporate GMP audit group for APIs and quality systems. She also developed, implemented, and maintained the GMP regulatory intelligence program for eight years at Amgen. This included surveillance, analysis, and communication of GMP-related legislation, regulations, guidance, and industry compliance enforcement trends. Unger was the first chairperson of the Rx-360 Monitoring and Reporting work group (2009 to 2014) that summarized and published relevant GMP- and supply chain-related laws, regulations, and guidance. She also served as the chairperson of the Midwest Discussion Group GMP-Intelligence sub-group from 2010 to 2014. She is currently the co-lead of the Rx-360 Data Integrity Working Group.

Barbara Unger formed Unger Consulting, Inc. in December 2014 to provide GMP auditing and regulatory intelligence services to the pharmaceutical industry, including auditing and remediation in data management and data integrity. Her auditing experience includes leadership of the Amgen corporate GMP audit group for APIs and quality systems. She also developed, implemented, and maintained the GMP regulatory intelligence program for eight years at Amgen. This included surveillance, analysis, and communication of GMP-related legislation, regulations, guidance, and industry compliance enforcement trends. Unger was the first chairperson of the Rx-360 Monitoring and Reporting work group (2009 to 2014) that summarized and published relevant GMP- and supply chain-related laws, regulations, and guidance. She also served as the chairperson of the Midwest Discussion Group GMP-Intelligence sub-group from 2010 to 2014. She is currently the co-lead of the Rx-360 Data Integrity Working Group.

Unger received a bachelor's degree in chemistry from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. You can contact her at bwunger123@gmail.com.