This Industrial Fungus Has Protein Expression Promise For Pharma

A conversation with Antti Aalto, Ph.D., VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland

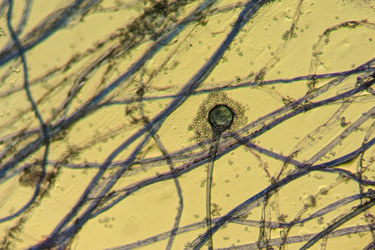

The next breakthrough in drug manufacturing might not come from a new lab discovery, but from organisms that have been quietly powering the food and industrial enzyme sectors for half a century, the filamentous fungi Trichoderma reesei.

The biopharmaceutical industry is often characterized by its reliance on a narrow set of workhorse expression systems, like CHO cells and E. coli. While these platforms are the bedrock of modern biologics, rising pressure to reduce CO2 footprints and slash the cost of goods (COGS) is driving a search for alternatives.

T. reesei is among a number of systems already well-characterized for large-scale industrial uses and food production now being re-evaluated for their potential pharmaceutical applications. These industrial veterans offer a level of robustness and productivity that traditional mammalian systems struggle to match. By leveraging decades of genomic data and established fermentation protocols from non-pharma sectors, some developers hope to bypass the growing pains typically associated with novel expression hosts.

As the industry looks toward decentralized manufacturing and “factory-in-a-box" concepts, the ability to use hardy, high-titer organisms becomes a strategic necessity. But, although T. reesei is a household name in the production of cellulases for textiles and food-grade enzymes, its transition into the highly regulated world of biopharmaceutical chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) represents a bold shift. Moving from industrial grade to pharma grade demands a rigorous look at genetic stability, downstream purification, and regulatory perception.

Still, the value proposition is clear: if a fungus can secrete over 100 grams of protein per liter for a laundry detergent enzyme, can it be engineered to produce high-quality monoclonal antibodies or fragments at a fraction of the current cost? The possibilities of this cross-industry migration are being explored at the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland. We met Antti Aalto, Ph.D., a research team leader at VTT, at the CHI PepTalk conference in San Diego, where he spoke about the nonprofit's recent exploration of pharmaceutical applications for T. reesei.

Aalto broke down the economic advantages of filamentous fungi and addressed why some green innovations — like agricultural waste feedstocks — might be a bridge too far for current pharmaceutical quality standards. The transcript below has been edited for clarity.

Can you give us a quick overview and describe T. reesei's economic and processing-related advantages?

Aalto: VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland is a nonprofit research organization that works with a lot of academics, industries, and companies. We have been working with this filamentous fungus, T. reesei, for more than 50 years, so we are quite familiar with it. This fungus was originally isolated for its cellulase activity. It secretes a lot of different enzymes into the extracellular space — mainly cellulases and hemicellulases — but more than 100 g/L.

We have harnessed that for our use in recombinant protein production. So, we are able to produce any kind of protein enzymes, food proteins, material proteins, and also pharmaceutical proteins using this fungus to efficiently secrete the proteins outside of the cell, which makes the downstream processing quite easy. This fungus is easy to cultivate, and the bioprocess is well established, so it doesn't need massive investment, and the costs are quite low.

Is T. reesei stability a concern? Specifically, how do you prevent expression cassettes from breaking down in the transition from small-scale bioreactors to commercial?

Aalto: Stability is not really a concern. Our expression cassettes are integrated into the genome. There have been reports of strain degeneration that sometimes happens at manufacturing scale — strains tend to lose their expression. This is understudied. There are different reasons why it may happen: genetic, epigenetic, bioprocess-related, morphology. But we think that, by selecting expression strains carefully and monitoring the bioprocess constantly, we should be able to avoid it. Some of our industrial partners using the fungus to express their industrial enzymes or their food proteins have not reported this to be a major problem.

You're exploring alternative feed streams like agricultural waste. Does your environmental impact analysis factor in pretreatment and extra purification to remove impurities?

Aalto: Some of our partners, for example in the food industry, are looking into using agricultural waste as feed stock with some success. However, for pharmaceutical proteins, this is not currently in the scope because the intense quality requirements would be too much of a hassle. Maybe in the future, if we were able to develop these technologies so they could be applied in low- and middle-income countries — local production of pharmaceuticals — then that could become something to focus on. But for pharmaceutical proteins, we don't really see that agricultural waste would be a viable feedstock at the moment.

Upstream, significantly higher titers can enable smaller facility footprints and fewer resources needed. What are some of the downstream benefits?

Aalto: Since the proteins are expressed into the culture broth, the downstream processing is quite straightforward. We don't need to lyse the cells, for example. With bacterial systems, you often need to do that. There's often quite a low amount of host proteins secreted along with the target proteins.

Also, we have made some initial economic assessments about the costs of producing pharmaceutical proteins at a commercial scale. Our results are telling us that the costs would be lower than what is currently used — what you can achieve currently with mammalian systems, such as CHO cells. We're somewhere below $20 U.S. per gram. We want to finish our calculations and publish this at some point soon, but we don't envision the costs to increase but rather go down. That's due to the fungus' high productivity and because the infrastructure is already there from this industrial enzyme manufacturing and other applications of this fungus. We believe that it would be quite easy to expand it to pharmaceutical projects, as well.

About The Expert:

Antti Aalto, Ph.D., is a research team leader at VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, a research organization owned by the Finnish government, where he develops and optimizes fungal production systems. He's a graduate of the University of Helsinki and performed postdoctoral research there and at the University of California San Diego.

Antti Aalto, Ph.D., is a research team leader at VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland, a research organization owned by the Finnish government, where he develops and optimizes fungal production systems. He's a graduate of the University of Helsinki and performed postdoctoral research there and at the University of California San Diego.