CAPA System Best Practices For GMP Compliance

By Thomas Peither, GMP-Verlag Peither AG

A CAPA system should be understood as an important element of the pharmaceutical quality system and implemented uniformly throughout the company or group. In principle, it can be implemented in two different ways: as an autonomous or as an integrated system. In this article, I’ll delve into the pros and cons of each, and I’ll also share some overall CAPA best practices.

Autonomous CAPA Systems

An autonomous CAPA system is characterized by its own documentation and schedule tracking. An autonomous SOP describes the process for the definition, responsibility, schedule tracking, and closing of CAPA activities. These are derived as possible follow-up activities to incidents that are regulated in other systems, such as for dealing with deviations, complaints, or self-inspections.

Based on a complaint, for example, a CAPA process is started in the independent CAPA system after its risk assessment - if necessary - and tracked using a separate documentation system.

Autonomous systems have a decisive advantage: Immediate measures can be taken to eliminate the deviation and prompt corrections can still be documented and processed within the triggering system, thus avoiding an inflationary generation of CAPA processes.

Another advantage of an autonomous system is a clear separation between the CAPA system and other processes. Each of the systems can thus be monitored, documented, and discussed on its own.

However, this also entails a disadvantage: The two separate processes must reference each other in order to link them clearly and comprehensibly. This always carries the risk of information being lost or transferred incorrectly.

In addition, similar events that might not be spectacular when viewed individually could turn out to be system weaknesses when viewed as a whole, which is more difficult to recognize when viewed separately.

IT-systems are, of course, helpful here. They each generate specific processes for the different activities, but they are interlinked and make all the information of the other process accessible.

Integrated CAPA Systems

An integrated CAPA system is usually somewhat simpler. That is a clear advantage. Here, at the end of the processing of the initial incident, corresponding CAPA measures are defined on the same documentation sheet and later their implementation is also documented. After handling both the problem and the CAPA measures, the responsible quality unit can evaluate and close both processes together.

This advantage, on the other hand, makes the process more complex: After the entire process has been finished, it must be transferred back to the quality unit for statistical evaluation (trend analysis, management review, etc.) and closing in the quality management system. Should there be concerns on the part of the quality unit, the system must grant the quality unit a right to reject. In this case, the procedure will be transferred back to the responsible unit in order to achieve an acceptable conclusion.

Important Aspects For Both CAPA Systems

Autonomous or integrated, for both variants, the description of the CAPA system should be made in the quality management manual together with the description of the systems for deviations, complaints, recalls, and so on.

In addition, a CAPA system requires its own SOP in which the procedures are defined together with the responsibilities and the necessary documentation.

It makes sense to prescribe a risk analysis following the investigation and processing of deviations and, consequently, the decision on the possible start of a CAPA activity.

No matter which result is reached, it is documented in any case that one has thought about a further measure in the sense of CAPA.

Three aspects are important here:

- prompt follow-up of the implementation,

- efficacy check, and

- reporting CAPA activities in the management review.

What Are The Characteristics Of An Effective CAPA System?

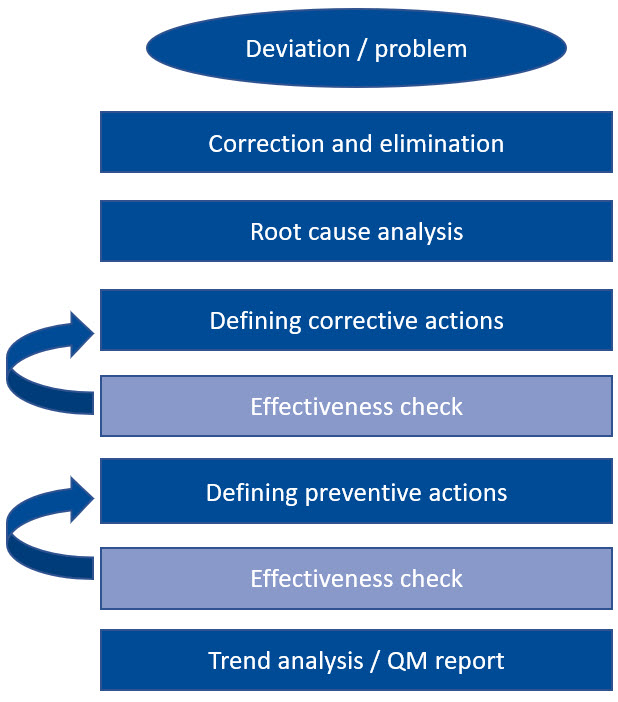

Ultimately, all effective CAPA systems are based on the same processes. When defining CAPA measures, it is important to determine how their effectiveness can be checked. For this purpose, objective criteria are needed that can be used to determine the result. If the measure taken does not show the expected success, a new corrective or preventive action must be considered. Therefore, a CAPA system is a continuous, iterative process that continues until it leads to a satisfactory result.

Let's look at such a system chain together: The very first action is always the immediate correction and elimination of the deviation, immediately followed by an investigation of the cause of the error. Once the cause has been identified, appropriate corrective actions are defined to prevent recurrence. Once these measures have proven to be effective and sustainable, this process is complete.

In principle, the same applies to preventive actions. Only when their effectiveness has been verified is a trend analysis carried out and everything recorded in the quality management report. Such a rigid and pragmatic approach not only sounds feasible, it is also extremely practical.

There are various reasons why CAPA systems have nevertheless quite readily gone off the rails at one time or are still going on. For example, as is so often the case when a new paradigm is introduced in pharmaceutical quality assurance, an enormous increase in CAPA measures was observed in the initial period when CAPA systems were established.

This was only partly due to an increased awareness of the relevant interrelationships. Much more frequently, it was simply due to misunderstandings, such as the assessment that every non-conformity must necessarily result in a CAPA measure. However, Chapter 1 of the EU GMP Guide does not stipulate the investigation of deviations or the initiation of CAPA measures for every non-conformity, but limits them to "relevant" deviations. It is therefore important to provide employees with sufficient training and to use examples to raise their awareness of what a deviation is and how it must be documented.

Whether a deviation documented on-site is further processed in the CAPA system or can be quickly corrected on-site is decided by a superior unit or by quality assurance. In any case, it must be regulated in the associated SOP.

Those involved in the process should definitely be involved in the evaluation of non-conformities, because they know the processes and interrelationships, have experience with possible causes, and should be able to make quick decisions.

The rapid evaluation or classification of an event in particular does not always have to be carried out by a higher-level quality department. The expert on-site is – at least according to European GMP understanding – equally authorized to help make decisions. As is often the case, the best decisions are made by all parties involved.

It is desirable, but so far only realized in a few companies, to link the instrument of prospective preventive action with other methods of continuous process improvement such as Six Sigma or Operational Excellence. Then, instead of being used routinely for every deviation, it could really only be applied specifically and with high priority after risk assessment.

3 Tips For Everyday GMP Life

- Make life a little easier for the decision-makers and add a selection of fixed CAPA measures at the end of the SOP for handling deviations, such as changes to work instructions, changes to processes, increase in testing or monitoring frequencies, change in responsibilities, or re-training of employees.

- Use the often-used standard "retraining employees" measure sparingly. A brief, direct instruction to employees as a corrective action is often more effective than formal retraining.

- If the same or a similar deviation occurs again and again, it is time to take a closer look. Make real corrections, take the time to rewrite a confusing, cluttered SOP. Simpler processes, procedures, guidelines, and documentation often bring lasting improvements.

This article is based on the GMP knowledge contained in the online portal GMP Compliance Adviser, which provides in-depth information about GMP best practices and regulations from Europe, USA, Japan, and many more (PIC/S, ICH, WHO, etc.).

About The Author:

Thomas Peither is a board member and head of marketing & business development at GMP-Verlag Peither AG, Schopfheim, Germany. Since 2008, he has also headed GMP Publishing Peither, Inc. He has more than 20 years of experience as a GMP consultant for pharma companies. He can be reached at thomas.peither@gmp-verlag.de.

Thomas Peither is a board member and head of marketing & business development at GMP-Verlag Peither AG, Schopfheim, Germany. Since 2008, he has also headed GMP Publishing Peither, Inc. He has more than 20 years of experience as a GMP consultant for pharma companies. He can be reached at thomas.peither@gmp-verlag.de.