Will Biosimilars Solve The Insulin Cost-Conundrum In The U.S.?

By Hamzah Aideed, principal analyst, Decision Resources Group (DRG)

In the United States, a national debate on drug pricing is taking place, with questions being raised about why U.S. patients pay some of the highest fees in the world to access prescription medicines. One drug class in the spotlight more than others is the insulins, as U.S. politicians put their pricing and the manufacturers that market them under scrutiny. To illustrate the extent of diabetes and insulin treatment in the United States, in 2017, more than 30 million people were classified as having type 1 or type 2 diabetes and, of them, approximately 7 million received at least one type of insulin treatment.1 Moreover, at least 80 million U.S. citizens are believed to have been in a prediabetic condition in the same year.2 As the U.S. prevalence of diabetes has increased over the past 10 years, average list prices of the most widely used insulin brands have tripled, while patients now pay twice the amount of out-of-pocket costs for insulin prescriptions.2

With the number of diabetes patients and insulin users forecast to grow, concerns around the cost of insulin treatment have become top-of-mind for patient advocacy groups, healthcare professionals, and policymakers. In recent times, a bipartisan effort in U.S. politics has brought insulin manufacturers forward to discuss the rising cost of insulins at congressional hearings. However, the dynamics of insulin pricing are convoluted, with different factors conspiring to create the situation the U.S. insulin market faces today.

The Current Insulin Landscape

There has been hope that the entry of “follow-on” insulins — a regulatory term that the FDA uses to define non-innovator insulins referencing originator brands — would have encouraged pricing competition among existing insulin products. However, this expectation has yet to become a reality. In developed pharmaceutical markets such as the United States, the insulin space is competitive, but it is dominated by three key players: Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi. Indeed, over 90 percent of the global insulin volume in 2018 was supplied by these three insulin manufacturers. Compared with the development of other therapeutic biologics, companies that are not yet established in the insulin space face several market barriers when pursuing the development and commercialization of insulins.

Challenges For Companies Developing Copycat Insulins

One such challenge for companies looking to develop the capability to make insulin products is the manufacturing process itself. Insulin production is expensive, most notably when recovering and purifying the final product after the fermentation process. Relative to the fermentation volume, the yield of insulin is low compared to other biologics; therefore, large bioprocessing volumes are required to make the production of an insulin product commercially viable. Developers will need large manufacturing sites to ensure adequate profit margins while meeting the global demand for insulins. Inevitably, the cost of development impacts the selling price, so companies long-established in the insulin market, with the required infrastructure already in place, are more flexible to offer competitive prices while maintaining a good return on investment.

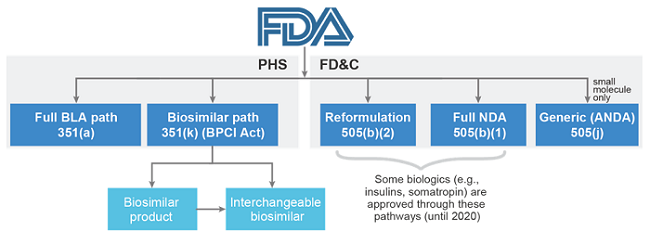

To complicate matters further, companies developing follow-on insulins are currently not permitted to submit them for regulatory review through the FDA’s biosimilars approval pathway. Instead, non-innovator insulins available on the U.S. market are not classified as biosimilars, but as follow-on biologics, since their reference brands were previously approved via a New Drug Application (NDA). NDAs, otherwise known as 505(b)(1) applications, regulate a number of biologics, including human growth hormones, follicle-stimulating hormones, and insulins. Follow-on biologics follow a similar, but shorter, NDA approval process referred to as 505(b)(2). Except for these therapeutic classes, the majority of other novel biologics are approved under a Biologics License Application (BLA), also referred to as the 351(a) pathway. Biosimilars are approved via an expedited version of a full BLA application, the 351(k) pathway. However, all biologics will be transitioned to the BLA pathway from March 23, 2020, meaning that all follow-on insulins can be approved as biosimilars after this date. Until then, this complex regulatory landscape is another market access hurdle that may have contributed to the lack of development and launch of follow-on insulins, compared to biosimilars launched in other markets and therapy areas.

Figure 1: FDA approval pathways (Source: Decision Resources Group4)

As of May 2018, only two follow-on insulins are available in the United States, both of which are marketed by two of the big three insulin manufacturers. It was hoped that the U.S. launch of the first follow-on insulin back in 2016, Eli Lilly’s Basaglar (insulin glargine), co-developed with Boehringer Ingelheim, would be offered at a much lower price compared to its reference brand, Lantus (marketed by Sanofi). Since then, Basaglar has yet to offer the high discounts that were previously expected. Sanofi’s Admelog (insulin lispro), launched in 2018, has also had low discounts relative to reference brand Humalog (marketed by Eli Lilly). The average list price of Basaglar and Admelog are approximately 15 percent less than their respective reference brands. This level of list price discount is lower than the average discount applied to U.S. biosimilars. For example, the list price of Renflexis, Merck and Co.’s biosimilar infliximab, which launched only months after Basaglar, is 35 percent less than J&J’s reference brand Remicade. Given the perceived high list price of these follow-on insulins, the companies that market them will need to offer further discounts to achieve market access in the United States.

Back in July 2017, the FDA gave tentative approval to the second follow-on insulin glargine, Lusduna Nexvue, which was to be marketed by Merck & Co. However, in October 2018, the company announced that it would no longer launch its insulin glargine product in the United States, or worldwide, for that matter. Although Merck & Co. provided little detail around the decision to withdraw Lusduna from the U.S. market, it is presumed that one major factor was the significant drug rebates being offered by the big three marketers of insulin products. For drugs such as insulin, with a high list price, companies may offer high rebates to gain placement on an insurance company’s formulary, commonly facilitated by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). PBMs are the go-between companies that negotiate with drug marketers to determine which medicines will make commercial insurance plans’ lists of covered drugs and how much insurers will pay for them. Rebates and discounts are paid by the drug marketers to the PBMs, which are often blamed for not passing on these savings to patients. While this reimbursement system may result in making such drugs more affordable for the healthcare insurers, the drug remains expensive for the uninsured, as well as for those with high cost-sharing insurance plans.

Eli Lilly Launches The First Authorized Generic Insulin

Following the recent congressional hearings, existing insulin manufacturers have already made moves to address the issue of rising insulin costs. During March 2019, Eli Lilly announced that the company is introducing a lower-priced authorized generic of its originator insulin lispro brand, Humalog, into the U.S. market. Eli Lilly has indicated that the list price of its authorized generic will be 50 percent lower than the current list price of Humalog and that it will be marketed under a different subsidiary brand. This strategy has been observed in other areas of the industry, with a recent example being Gilead launching authorized generics of its hepatitis C drugs Harvoni and Epclusa at a 75 percent list price discount to the brands, under its subsidiary company Asegua Therapeutics. Like Gilead and other companies that have adopted this strategy, Eli Lilly has done so under growing political and public pressures to lower its drug prices.

However, this pricing strategy could also be an opportunity for Eli Lilly to protect its market share from oncoming competition from non-innovators and, perhaps eventually, biosimilars of its insulin drugs. Conversely, Eli Lilly’s recent moves could be viewed as anticompetitive for companies wishing to make copycat versions of its insulin products, because competing with such prices may compromise an insulin developer’s opportunity to make a meaningful return on investment.

Sanofi To Offer Better Savings For Insulin Patients

In the wake of the insulin price debate, Sanofi has also taken measures to improve access to its insulin drugs, via its Insulins Valyou Savings Program. This subscription model had existed previously; however, patients were required to pay $99 for one vial or $149 for a box of 10 vials. As of April 2019, Sanofi has revised this patient access program so that patients pay $99 a month for up to 10 boxes and/or 10 vials per month. Moreover, Sanofi has indicated that the expanded program is intended for anyone paying high prices out-of-pocket, and there is no income eligibility requirement.

Other companies are also adopting similar programs. To use Gilead again as an example, the company signed a contract with the Louisiana Department of Health in March 2019 to set up a purchasing agreement for its Epclusa authorized generic, whereby Medicaid patients will pay a fixed amount for unlimited access to the drug for five years. Other states are now in pursuit of such deals. Sanofi’s and Gilead’s subscription concepts to curb patient out-of-pocket costs have been likened to a Netflix-style model. Some industry analysts believe that payment models like Sanofi’s and Gilead’s could provide a better alternative to regulate and lower drug costs for U.S. citizens, as it is argued that the availability of biosimilars and follow-on biologics has not been effective enough to achieve meaningful savings.5

Outlook For Insulin Biosimilars

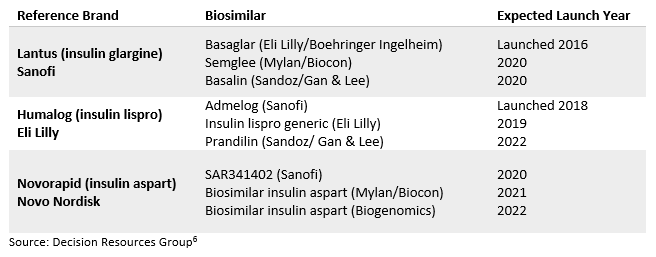

With the deadline fast approaching for a regulatory opening to biosimilar versions of insulin on March 23, 2020, there are still many industry observers who believe that as other pharmaceutical companies referencing originator brands enter the insulin market, price reductions may begin to occur. In addition to existing follow-on insulins being transitioned to biosimilars in March 2020, a small number of companies are also developing biosimilars to launch in the United States on or after this date. Ahead of the pack is Mylan and its commercial partnership with insulin manufacturer Biocon. Mylan has already launched its insulin glargine biosimilar, Semglee, in Europe, and is expected to launch in the United States in 2020. Another notable company is Sandoz, which has already commercialized a number of biosimilars but previously lacked an insulin pipeline. However, late in 2018, Sandoz formed a strategic commercial partnership with Chinese manufacturer Gan & Lee, which already has biosimilars of insulin glargine and insulin aspart as part of its drug portfolio. This partnership will allow Sandoz to expedite its market entry of competing biosimilars. Under this agreement, Sandoz will market these insulin biosimilars in the United States, as well as other regions, including Europe, Japan, South Korea, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Table 1: Insulin Biosimilars Pipeline in the United States

Although the current pipeline of biosimilar insulin development is small relative to other reference biologics, it is hoped that the FDA’s upcoming streamlined regulatory pathway could increase the development of U.S. insulin biosimilars. Biosimilar companies no longer have to wait for the March 2020 transition to begin developing biosimilars of insulins that were previously approved via the NDA pathway. Although large insulin companies such as Eli Lilly and Sanofi have taken steps to improve access to insulins for U.S. diabetes patients, most agree that more needs to be done to reduce the cost of insulin products. In time, we will see if these recent reforms will help to address the challenge at hand. It is likely that increased insulin competition from biosimilars, provided that more make it onto the U.S. market and do not fold like previous candidates (e.g., Merck & Co.’s Lusduna), will help to stimulate more competitive pricing.

References:

- Cowie CC, et al. Medication use and self-care practices in persons with diabetes. Diabetes in America, 3rd ed. National Institutes of Health, 2017 (NIH publ. no. 17-1468)

- Decision Resources Group, Diabetes Insights, 2018

- Hua X, et al. Expenditures and prices of antihyperglycemic medications in the United States: 2002-2013. JAMA 2016; 315:1400–1402

- Decision Resources Group, Biosimilar Insights, 2019

- Trusheim M, et al. Biologics are natural monopolies (part 1): why biosimilars do not create effective competition. Health Affairs. 15 April 2019. 10.1377/hblog20190405.396631. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20190405.396631/full/. (Accessed May 2, 2019).

- Decision Resources Group, Biosimilar Insights, 2019: https://decisionresourcesgroup.com/solutions/market-assessment-suite/understand-the-market-potential-with-biosimilars/

About The Author:

Hamzah Aideed is a principal analyst and part of the biosimilars team at Decision Resources Group, conducting both primary and secondary market research to provide in-depth analysis and key insights into biosimilars and the biopharmaceutical industry. Prior to joining DRG, he was with Consulting at McCann Health, specializing in the design and execution of advanced qualitative and quantitative research methodologies. Aideed holds an M.Sc. in biotechnology, bioprocessing, and business management from the University of Warwick, and a B.Sc. in biological chemistry from Aston University. He provides his research on the market assessment of biosimilars on Decision Resources Group’s Insights Platform.

Hamzah Aideed is a principal analyst and part of the biosimilars team at Decision Resources Group, conducting both primary and secondary market research to provide in-depth analysis and key insights into biosimilars and the biopharmaceutical industry. Prior to joining DRG, he was with Consulting at McCann Health, specializing in the design and execution of advanced qualitative and quantitative research methodologies. Aideed holds an M.Sc. in biotechnology, bioprocessing, and business management from the University of Warwick, and a B.Sc. in biological chemistry from Aston University. He provides his research on the market assessment of biosimilars on Decision Resources Group’s Insights Platform.