What's In A Name? Understanding Unmet Medical Need May Help Align Prioritization Strategies

By Sandra Blumenrath and Inka Heikkinen, DIA

Unmet medical need (UMN) is not a new concept, but it is an increasingly important one. Regulators and payers are nudging the industry to steer R&D investments toward areas with higher unmet need and less crowded pipelines. Current regulatory incentives designed to move this trend forward include Breakthrough Therapy1 and Fast Track2 designations in the U.S.; Sakigake designation in Japan;3 and Priority Medicines (PRIME) scheme,4 accelerated assessment,5 and conditional marketing authorization6 in Europe. Additionally, many countries have their own expedited pathways that apply the UMN concept. Still, investment in this area has not taken off as expected.

In the U.S., regulatory incentives are not motivating the industry to develop treatments that address an existing UMN;7 instead sponsors focus on areas like oncology that, based on treatment pricing and disease prevalence, yield bigger estimated returns. In Europe, some European Medicines Agency (EMA) experts made similar observations when assessing so-called “white spots” in global development pipelines.8 While oncology does have a few white spots that get less attention from developers, there are plenty of other areas with major treatment development needs, such as CNS therapy, psychiatric disorders, and infectious diseases.

Looking at the latest PhRMA pipeline report from 2017, oncology attracted most R&D investment, with 7,392 potential first-in-class products in the pipeline, while psychiatry had only 379.9 The number for infectious diseases is slightly more encouraging: here, first-in-class projects climbed to a total of 1,509. The EMA has experienced a similar trend: 59 applications submitted to PRIME were in oncology therapy areas, while only three were submitted in psychiatry. Infectious diseases received 15 applications, with only two meeting the criteria of existing UMN and the product’s potential to address it.

Given the long development times of pharmaceuticals, after only six to 10 years of expedited regulatory pathways, it might be too early to expect big shifts in R&D investment. This is especially true considering the long-standing political attention that has driven cancer research ever since the National Cancer Act was signed into law by President Richard Nixon in 1971.

Making The Shift

To make a shift that aligns prioritization globally, the question arises whether UMN is defined clearly enough and has the right incentives in place to allow industry decision makers to take the risk and invest in areas with higher UMN. Medicine developers are faced with prioritization early on, when deciding which development program to focus their funds on. And regulators, payers, and health technology assessment (HTA) agencies have their own considerations of what meets the criteria of UMN and what mechanisms can be used to make such medicines available.

Current HTA, for example, emphasizes the size of benefit. Payers, on the other hand, expect breakthrough medicines to address UMNs and are ready to pay for them. But, they are not willing to pay for an incremental increase in benefit over existing standard of care, even for disease areas where the burden of the existing treatment is high. Regulators offer development support for products addressing UMNs that show major promise in the first studies conducted on patients.

A good example where decision makers have aligned is Novartis’ breakthrough medicine for acute lymphoblastic leukemia drug Kymriah, which has shown that payers in the U.S. and Europe are ready to pay for the promise or hope the drug brings, even if the long-term benefit, which is uncertain at the time of regulatory approval, may ultimately be at par with the current standard of care (such as bone marrow transplants). However, not every product that has the potential to address an unmet need in the eyes of regulators is considered cost-effective by HTA bodies and payers. Therefore, innovation may not be rewarded with a predictable return — the ultimate goal of innovator industry. A recent example of this dilemma is another CAR T-cell product, Gilead’s Yescarta. This drug was deemed to have low cost-effectiveness by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (the U.K. HTA body), forcing the company to re-evaluate its pricing in order to reach agreement with the U.K.’s National Health Service.

One obvious question is whether the innovative first-in-class products addressing unmet needs should be rewarded more highly for paving the way for subsequent products that often emerge only a few years later and with better benefit-risk profiles. But another, at least equally important, question is whether the current definition of UMN ensures predictability of investment returns globally. Does it enable risk-taking in an area of higher need if the opportunity cost is a cancer medicine with a higher likelihood of returning the investment?

Although the concepts of UMN articulated by the different stakeholders may not necessarily differ widely, stakeholders do prioritize differently, making it difficult to strike a balance between sponsor goals, patient needs, and societal priorities. This not only confuses patients but also raises the question of how continuity in the value of new medicines can be guaranteed at each step of the drug development process, from R&D to patient access. Providing clarity around the criteria rather than a one-size-fits-all approach to defining UMN may hence be the most promising path toward aligned prioritization among all stakeholders, nationally and internationally, granting the flexibility to satisfy the unique needs of each.

Addressing Current Definitions And The Need For Alignment

At two recent flagship healthcare product development conferences (DIA Europe 2018 and DIA Global Annual Meeting), the Drug Information Association (DIA) in collaboration with the Centre for Innovation in Regulatory Science convened multi-stakeholder working groups. These groups of industry, regulator, HTA body, payer, patient, and academia representatives met to identify and discuss the perspectives of the different stakeholders and the different definitions used and to establish a common but flexible set of criteria that captures everyone’s needs and priorities. Two publications with detailed findings from these working groups will soon be available as peer-reviewed articles. Here, we briefly discuss some of the main findings.

Definitions And Stakeholder Perceptions

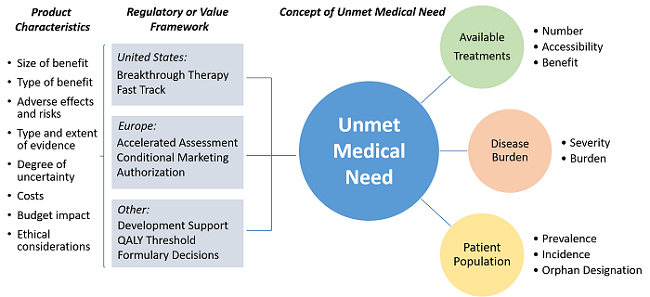

A formal literature review of 34 online resources as well as face-to-face roundtable discussions with stakeholders yielded more than 15 definitions of UMN, each with a different set of elements. Three of the most common elements in these definitions were availability (and adequacy) of treatments, disease severity or burden, and size of the affected population. While there were important differences, all definitions could be grouped into three main categories based on these three elements:

- Of the three most common elements, the definition only includes availability (and adequacy) of treatments.

- The definition includes both availability (and adequacy) of treatments and some form of disease severity or burden.

- The definition includes all three elements, i.e., availability (and adequacy) of treatments, some form of disease severity or burden, and the size of the affected population.

Despite these commonalities, important differences were observed in how stakeholders ranked the various criteria. Interestingly, burden of treatment — which affects adherence and compliance — was ranked more highly by regulatory representatives than by patient representatives. The latter regarded this as an especially low priority for rare diseases without currently available treatments as well as for more common diseases for which only few or essentially ineffective treatments exist (such as Alzheimer’s disease). Availability of treatments and disease severity or burden were ranked highly by all stakeholders, although the availability of a treatment was overall considered a primary element. The biggest differences among stakeholders, especially between industry and regulators, were not the elements themselves but the way they were interpreted. Definitions included phrases such as “significant benefit” or “adequate treatment” without offering any guidance on how they should be measured. At the DIA Global Annual Meeting, however, an FDA representative explained that the agency considers the totality of evidence when assessing whether a product meets the criteria for addressing a UMN.

Unmet medical need (UMN) elements and product characteristics considered in regulatory and value frameworks when deciding upon a product addressing UMN.

Recommended Elements—Common Ground and Flexibility

Although stakeholders in these working groups strived to develop a common definition based on the most common elements, they also recognized that any attempt to appropriately quantify UMN depends on the scope and regulatory or value framework in which the different stakeholders apply the UMN concept. In other words, the definition itself cannot be completely divorced from the framework within which it is used. For example, the availability of a treatment could be measured either as the sheer number of treatments available to patients or as their accessibility, affordability, or overall benefit over other treatments.

This is also why, overall, stakeholders preferred an aligned set of elements, rather than an entirely harmonized one. An aligned set would allow for some degree of flexibility depending on stakeholder needs as well as flexibility nationally and internationally, making the approval and access pathway of novel therapeutics more predictable. Harmonized elements, meanwhile, may result in unnecessary restrictions and ultimately hamper the development, authorization, and reimbursement of new treatments that meet UMNs.

Conclusion

Across regions and stakeholders, there are diverse approaches to assessing UMN for prioritizing pharmaceutical R&D. Although many stakeholders do not have an official definition for UMN, most have agreed on a handful of key elements. What is particularly promising for a path toward aligned prioritization is that there seems to be general agreement on these key elements and — at least to some extent — how they are weighted.

Although the two working groups operated under informal, semi-open-exchange conditions with representatives who (with few exceptions) were neither specially curated nor randomly selected, the overall findings provide a solid qualitative assessment of the UMN definitions and elements used across different stakeholders. Going forward, DIA will continue to facilitate the discussion to achieve stakeholder alignment on a treatment’s eligibility for accelerated development and patient access pathways. This will incentivize stakeholders to explore new ways to deliver affordable treatments addressing UMNs and, in turn, impact pricing and reimbursement decisions globally.

References:

- https://www.fda.gov/ForPatients/Approvals/Fast/ucm405397.htm

- https://www.fda.gov/forpatients/approvals/fast/ucm405399.htm

- https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/health-medical/pharmaceuticals/140729-01.html

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/human-regulatory/research-development/prime-priority-medicines

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/marketing-authorisation/accelerated-assessment

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/human-regulatory/marketing-authorisation/conditional-marketing-authorisation

- http://www.pharmexec.com/meeting-unmet-medical-needs-disparity-dilemma-0

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1586/17512433.2015.1028918

- http://phrma-docs.phrma.org/files/dmfile/Biopharmaceutical-Pipeline-Full-Report.pdf

About The Authors:

A biologist by training, Sandra Blumenrath, Ph.D., M.S., serves as science writer for DIA. Blumenrath brings extensive experience in scientific research, education, and communication to her role at DIA, where she produces scientific and healthcare-related content for a variety of audiences. Blumenrath graduated with an M.S. from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, and earned her Ph.D. at the University of Maryland, College Park. Prior to joining DIA, she worked as a scientist, an educator, and a content developer at the University of Maryland, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

A biologist by training, Sandra Blumenrath, Ph.D., M.S., serves as science writer for DIA. Blumenrath brings extensive experience in scientific research, education, and communication to her role at DIA, where she produces scientific and healthcare-related content for a variety of audiences. Blumenrath graduated with an M.S. from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, and earned her Ph.D. at the University of Maryland, College Park. Prior to joining DIA, she worked as a scientist, an educator, and a content developer at the University of Maryland, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Inka Heikkinen is associate director of scientific programs at DIA (Europe), a not-for-profit connecting top leaders from all sectors in healthcare. In her role, Heikkinen works with KOLs from EMA, CHMP, HMA, EUnetHTA, and payer organizations, facilitating discussions about the challenges they face. Before her role at DIA, Heikkinen worked in life science policy and regulatory roles in London, Brussels, and Finland, liaising closely with European Commission officials and health authorities. She has a master’s degree in health and pharmacoeconomics from Barcelona School of Management, Spain, and in policy from City, University of London, U.K., accompanied by regulatory studies from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.

Inka Heikkinen is associate director of scientific programs at DIA (Europe), a not-for-profit connecting top leaders from all sectors in healthcare. In her role, Heikkinen works with KOLs from EMA, CHMP, HMA, EUnetHTA, and payer organizations, facilitating discussions about the challenges they face. Before her role at DIA, Heikkinen worked in life science policy and regulatory roles in London, Brussels, and Finland, liaising closely with European Commission officials and health authorities. She has a master’s degree in health and pharmacoeconomics from Barcelona School of Management, Spain, and in policy from City, University of London, U.K., accompanied by regulatory studies from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark.