Should You List All Manufacturing Facilities In Your Drug Substance Application? Understanding The Supply Chain

By Ketan Agravat, rK3 Solutions

This two-part article addresses the importance of listing of drug substance manufacturing facilities in a drug application and discusses the role of regulatory professionals in ensuring the security and integrity of the drug supply chain. Here in Part 1, we will review the significance of listing facilities in a drug application — namely, how it connects the dots in the supply chain from a raw material manufacturer to the distributor, manufacturer, packager, wholesaler (which may involve multiple agencies), pharmacy, and finally, the patient, helping to effectively manage supply chain integrity.

In Part 2, we will turn our attention to regulatory professionals, who play a critical role in preparing the list of all the facilities involved in the drug manufacturing that should be included in drug application, as they can envisage the importance of a facility to the security of the drug supply chain and lay down a broader picture. This is achieved by providing factual, correct, and current information in the drug substance section of the drug application.

Supply Chain Security And Integrity

The Guidelines on Good Distribution Practice from the European Commission, the Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA) from the U.S. Congress, and the U.K. Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency’s (MHRA) recent announcement on supply chain integrity in its five year corporate plan, all authorize regulatory authorities to strengthen the supply chain and increase access to suppliers’ databases, by maintaining traceability of such.

In a warning letter to McKesson Corp. dated Feb. 7, 2019, the FDA noted, “This warning letter summarizes significant violations of the verification requirements found in section 582(c)(4) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) (21 U.S.C. 360eee(c)(4)). These verification requirements are intended to help preserve the security of the supply chain for prescription drug products, thereby protecting patients from exposure to drugs that may be counterfeit, stolen, contaminated, or otherwise harmful. The verification requirements at issue include those that apply to wholesale distributors when they determine or are notified that a product is suspect or illegitimate.”1 This statement lays out the very importance of supply chain integrity.

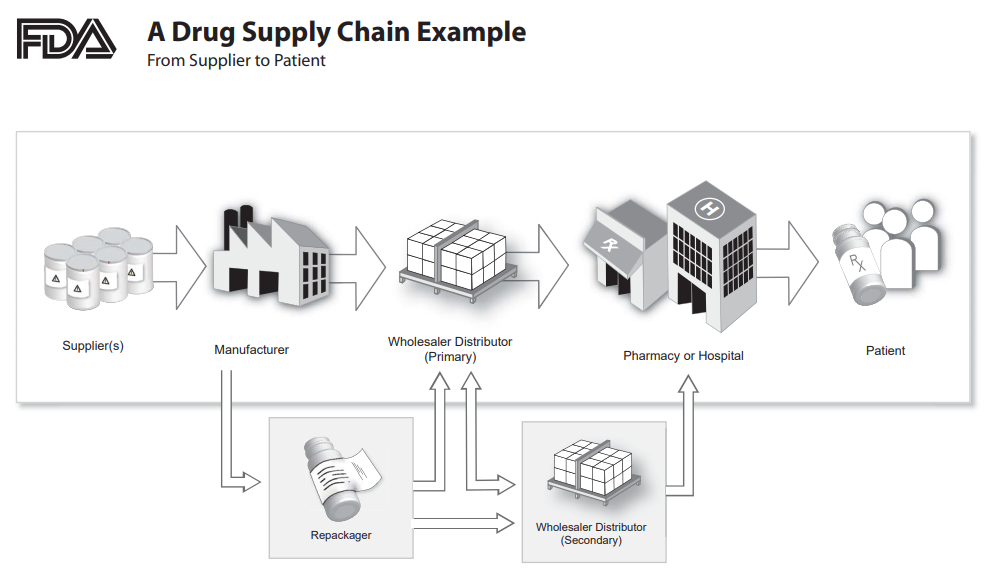

The drug supply chain is complex, and it is becoming increasingly more so with the involvement of more players and emerging markets, along with the new manufacturers from those markets. Figure 1 illustrates how long and complex the global supply chain is, especially when taking into account that more than 100 countries produce pharmaceutical raw materials.

Figure 1: An overview of the drug supply chain2

Suppliers, manufacturing facilities, and analytical facilities are essential elements of supply chain integrity. To make it even more complex, it may also involve contractors, subcontractors, repackagers, and multiple wholesalers and distribution centers as well as the already elongated/intricate distribution chain.

The USP general chapter <1083> Good Distribution Practices — Supply Chain Integrity3 recommends the following:

- Confirm the name(s) and geographic location(s) of suppliers and their subcontractors

- Investigate the company’s reputation, and determine if it is a subsidiary of a larger company

- Establish that the supplier is registered with its national regulatory authorities and is licensed to manufacture pharmaceutical ingredients (not bulk chemicals)

- Determine whether subcontractors are used by suppliers and for what purpose, and establish their identity

- Establish procedures to prevent tampering during shipment, e.g., tamper-evident embossed tape on boxes and drums or numbered seals on bulk materials

- Verify or test the products, goods, or materials throughout the supply chain, e.g., by verification or testing at certain supply chain stops/points

- Verify the shipping documentation associated with the imported product or material, i.e., its chain of custody

- Be alert to signals/events/disruptions in the environment or changes in the supplier’s organization that may negatively impact suppliers, subcontractors, or the products, goods, or materials

- Be alert to information that could indicate counterfeiting or other fraudulent activities such as offers to sell the product at a price significantly below market value.

Failure to develop the knowledge as to where raw materials (drug substance starting material, intermediates, or the drug substance itself) are being manufactured increases the risk of supply chain failure. It’s show factory vs. shadow factory in many cases, where the material may be produced in a non-GMP compliant manner at a factory that may not be under the direct control of the registered/qualified manufacturer/supplier.

A review of the GDUFA (Generic Drug User Fee Amendments of 2012) facilities listed with the FDA reveals that ~883 active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) manufacturers are registered under GDUFA II: FY 2020: Self-Identified Generic Drug Facilities, Sites and Organizations.4 Out of these, ~88 percent, i.e., 775 facilities, are outside the U.S. I believe this list does not include intermediates and starting material manufacturers, as most of them are not covered under the GDUFA. This list will grow significantly when manufacturing facilities covered by the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), biosimilars, and other components of the healthcare industry are included, making it more complex in terms of drug supply chain.

Conclusion

The health care value chain is a complex network of manufacturers, distributors, wholesalers — all the way through to the patient/consumer. Everyone in the health value chain shares a moral imperative to improve access to medicines for patients.

Pharmaceutical products supply chain, cornerstone of healthcare system, is like a labyrinth; irregular and twisting and very complicated. Its component varies from organization to organization without its structure.

In the current era of global manufacturing system and global distribution, it is equally important to maintain proper database for supply chain component.

References:

- https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/warning-letters/mckesson-corporation-headquarters-2719-565854-02072019

- https://www.fda.gov/media/81739/download

- https://www.uspnf.com/sites/default/files/usp_pdf/EN/USPNF/revisions/c1083.pdf

- https://www.fda.gov/media/124398/download

About The Author:

Ketan Agravat is founder of rK3 Solutions, a regulatory consulting firm based in India. He has more than 25 years of experience in regulatory and quality functions related to active pharmaceutical ingredients. Having worked for multiple manufacturing companies over 20 years, he now serves small pharmaceutical manufacturers with the goal of helping them provide the best quality APIs/intermediates, including the supply of clinical trial materials to innovator companies. He is also engaged with educational institutions in guiding students on regulatory functions in the pharmaceutical industry. He can be contacted at ketanagravat@gmail.com.

Ketan Agravat is founder of rK3 Solutions, a regulatory consulting firm based in India. He has more than 25 years of experience in regulatory and quality functions related to active pharmaceutical ingredients. Having worked for multiple manufacturing companies over 20 years, he now serves small pharmaceutical manufacturers with the goal of helping them provide the best quality APIs/intermediates, including the supply of clinical trial materials to innovator companies. He is also engaged with educational institutions in guiding students on regulatory functions in the pharmaceutical industry. He can be contacted at ketanagravat@gmail.com.