IVDs And LDTs: Evolving Visions Of FDA Oversight Under The VALID Act

By Blake E. Wilson, Hogan Lovells

On Dec. 6, 2018, U.S. lawmakers released a discussion draft of the Verifying Accurate, Leading‑edge IVCT Development (VALID) Act. The draft bill sets out a regulatory framework for a new product paradigm called in vitro clinical tests (IVCTs), which would cover an array of clinical tests, including laboratory developed tests (LDTs) and traditional in vitro diagnostics (IVDs) assays sold to laboratories by manufacturers.

The VALID Act represents the latest development in LDT regulation, an area that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and Congress have grappled with for over 30 years. Below is a brief history of how clinical tests have been regulated, followed by an overview of the proposed VALID Act, and where the potential legislation stands.

Background

FDA currently regulates IVDs as medical devices based on their use in the medical care of patients [Section 321(h) of the Food Drug and Cosmetic (FDC) Act]. Historically, FDA has refrained from actively regulating LDTs and many have asserted that the Agency does not have jurisdiction to do so. In parallel, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) regulate laboratory operations, pursuant to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA).

Over the past 30 years, FDA has occasionally attempted to assert authority to regulate LDTs, principally through Agency guidance. This occurred most recently in 2014, when the Agency proposed a new LDT framework modeled after FDA’s regulation of IVDs, via guidance document. However, due to significant stakeholder concerns and a change in the administration, FDA withdrew the proposed framework in November 2016.

In an attempt to clarify the regulatory framework for LDTs, U.S. Reps. Larry Bucshon (R – IL) and Diana DeGette (D – CO) circulated a draft of the Diagnostic Accuracy and Innovation Act (DAIA) in March 2017, which proposed new statutory authorities for oversight of LDTs. After the draft DAIA was circulated, FDA provided technical drafting assistance and circulated a revised version in August 2018 (TA feedback). The draft VALID Act, which was circulated by Reps. Bucshon and DeGette, as well as U.S. Sens. Michael Bennet (D – CO) and Orrin Hatch (R – UT), builds upon FDA’s TA feedback, accepting several key recommendations from the Agency.

VALID Act Regulatory Framework

According to the bill’s authors, the VALID Act “would establish a risk-based approach to IVCT regulation, prioritizing FDA resources for the highest-risk level tests that expose patients to serious or irreversible harms.”

Under the VALID Act, IVCTs would constitute a new medical product regulated separately from drugs, devices, and biologics. Unlike the earlier draft DAIA, the draft VALID Act does not require the creation of a new center within FDA dedicated to regulating IVCTs, and it is possible that oversight could fall to the Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH).

A.IVCT Definition

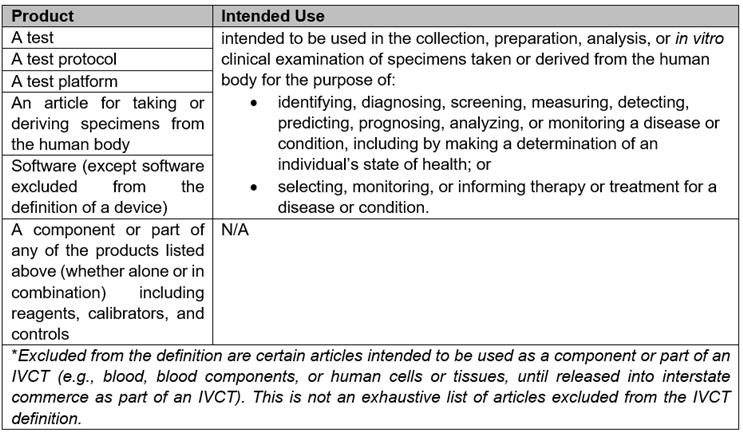

IVCT, as defined by the draft bill, is a broad-ranging product category with several carveouts. A summary table of the products covered by the IVCT definition is provided below:

B.Risk Classification

The draft VALID Act currently includes definitions for high-risk and low-risk IVCTs. High-risk IVCTs generally would be subject to premarket approval unless otherwise exempted. Low-risk IVCTs, as well as other types of IVCTs identified in the draft bill, would be exempt from premarket approval, but in most cases would need to adhere to notification (i.e., listing) and other requirements applied to IVCTs [e.g., quality system (QS), adverse event (AE) reporting, etc.].

High-risk and low-risk are defined according to the type of harm that would likely occur in the event of an undetected or inaccurate result, taking into account whether mitigating measures could be used to reduce the risk of harm to an acceptable level.

C.Marketing Pathways

Premarket approval is applicable to IVCTs unless exempted and the bill exempts several categories of IVCTs from premarket approval (grandfathered tests, tests that would have been exempt from 510(k) notification, low-risk tests, etc.).

An IVCT premarket approval application would include many of the same components as a premarket approval application under 21 C.F.R. § 814.20, as well as additional information identified in the draft bill (e.g., applicable mitigating measures, and information regarding methods / facilities / controls used in developing the testing). To approve the premarket approval application, the developer must demonstrate a reasonable assurance of adequate analytical and clinical validity.

Priority review would be available for developers of an IVCT that provides more effective treatment or diagnosis of a life-threatening or irreversibly debilitating human disease or condition, and is either novel (e.g., represents breakthrough technology or no alternatives exist) or it is in the public’s best interest to make the test available. Although IVCTs approved for priority review would be exempt from the premarket approval requirements and would be eligible for approval under the Breakthrough pathway, it should be noted that a Breakthrough IVCT designation appears to be separate from priority review.

The definition of a Breakthrough IVCT and the regulatory requirements associated with designation still need to be added by the bill’s authors, so it is not clear whether the regulatory burden would be meaningfully reduced compared to the premarket approval pathway.

Marketing pathways other than premarket approval would also be available for IVCTs under the VALID Act, including, among others, precertification, grandfathering, and rare-disease.[i] The precertification program is of particular interest to industry because it would enable eligible test developers to obtain a precertification for a single technology (i.e., test method). After obtaining the precertification order, eligible IVCTs that fall within the scope of the order would be exempt from premarket review. The initial precertification order is valid for two years, and is eligible for renewal thereafter.

To obtain a precertification order from FDA, the requesting sponsor must meet the eligibility requirements and file a precertification application for the technology that meets the statutory threshold for approval. In general, a sponsor is ineligible to apply for precertification if they have committed significant violation of the FDC Act or PHS Act, unless otherwise specified. The precertification application includes, among other things:

- information about the sponsor

- information about the methods, facilities, and controls to be used

- procedures for analytical and clinical validation

- information for one or more representative IVCTs that would fall under the scope of the precertification order, one of which must be the “highest complexity test to validate and run within the developer’s stated scope.” The information required for this representative “highest complexity test” is essentially the same as a premarket approval application, except raw data is not required.

To receive a precertification order, the developer must establish, among other things, that:

- there is a reasonable assurance of adequate analytical and clinical validity for all eligible IVCTs within the proposed scope of the order

- the methods, facilities, and controls used for development of IVCT within the proposed scope of the order meet the QS requirements

- the representative test could be approved under the premarket approval provisions

In many circumstances, tests offered before the enactment of the VALID Act would be eligible for exemption from several of the draft Act’s requirements, including premarket approval, QS requirements, and labeling requirements. Such tests, termed “grandfathered tests,” would need to meet the following criteria:

- developed and introduced into commerce at least 90 days prior to enactment of VALID Act

- not previously reviewed by FDA

- developed by CLIA certified lab

- as of the 90-day pre-enactment cutoff, the test has not been modified in such a way that it would qualify as a new test

Developers of grandfathered tests would not be exempt from all aspects of the VALID Act, including incorporating mitigation measures that become applicable to the test category. Developers will also be required to maintain documentation that demonstrates their device qualifies for such classification, including that it has not been inappropriately modified. Some modifications that would qualify as creating a new test include:

- modifications that change the test group (e.g., the substance(s) to be measured, test method, test purpose, etc.)

- modifications that change performance claims

- modifications that cause the device not to comply with mitigating measures or restrictions on the test

D.Quality System and Adverse Event Reporting Requirements

The draft VALID Act provides QS requirements that will be applicable to all IVCT developers, except under limited circumstances. The general components of the VALID Act QS requirements track closely to the quality system requirements for medical devices found in 21 C.F.R. Part 820, and the draft bill would simply instruct FDA to amend Part 820 as necessary to apply the QS requirements to IVCTs as provided in the draft bill.

Interestingly, if enacted, the draft VALID Act would apply the full requirements of Part 820 to IVCTs while FDA undertook the process of amending the requirements to be tailored to IVCTs. However, the draft bill does not provide a deadline by which FDA must amend Part 820 for application to IVCTs and, in theory, Part 820’s full requirements could apply to IVCT developers for several years after the VALID Act’s enactment.

The draft VALID Act takes a similar approach to adverse event reporting by stipulating that the medical device adverse event reporting requirements under 21 C.F.R. Part 803 would apply to IVCT developers until such time as the regulations are amended to implement reporting requirements specific to IVCT developers. While the definition of a reportable event is similar to Part 803, the timelines for reporting such events differ significantly in the draft VALID Act.

Under the draft VALID Act, like Part 803, developers would be responsible for reporting deaths and serious injury that the test reasonably caused or contributed to, as well as cases where malfunction occurred in the IVCT that would likely cause or contribute to a death or serious injury if the malfunction were to recur. However, under the draft VALID Act, an adverse event need not be reported if it is directly attributable to a laboratory error.

In addition, while the draft bill requires reporting within five calendar days for events that involve a patient death or reasonably suggest an imminent threat to public health (Part 803 provides a 10-day reporting period), all other adverse events would be reported quarterly. By contrast, Part 803 requires monthly reporting for all reportable events that do not need to be submitted sooner.

Impact of Gottlieb’s Departure on the VALID Act

After spearheading the TA document, FDA Commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb resigned from the Agency. During his tenure as Commissioner, Gottlieb maintained that the Agency lacked the legal authority to regulate the LDT sector and, currently, there appears to be a consensus that any modification to the regulatory status of LDTs will require legislative action. Yet, the departure of a key architect and prominent advocate could slow the VALID Act’s progress.

As hinted by Gottlieb in an interview given shortly before his departure, “I'm hopeful [that the LDT bill will] happen within the next twelve months and not sit out there waiting for another PDUFA cycle to put onto a PDUFA bill [in 2022].”

This concern was all but confirmed by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (“HHS”), which issued a TA on the VALID Act discussion draft.[ii] For the most part, HHS supports the VALID Act’s approach to LDT regulation — in particular, provisions regarding FDA oversight of IVCTs, implementation of priority review and precertification, and exemptions for grandfathered tests. HHS also suggested certain additions and edits to the bill, including (1) premarket pathways for certain types of tests that would only require abbreviated premarket review, and (2) an expanded user fee program that would create fee opportunities throughout the product lifecycle.

As indicated above, HHS suggested that authorization of the VALID Act be aligned with Medical Device User Fee Amendments (MDUFA) reauthorization — not slated to take effect until 2022 — so its funding structure can be reliably implemented.

Conclusion

The VALID Act, as proposed, represents a paradigm shift in how FDA regulates clinical tests. While the regulatory framework imagined in the draft bill draws upon FDA’s current medical device regulatory framework, there are portions of the bill tailored to easing the regulatory pathway for IVCTs.

In a Dec 6, 2018, FDA press release regarding the future of clinical tests,[iii] the Agency stated that, under the right regulatory framework, only 10 percent of tests should require premarket review. Further, FDA believes that 40-50 percent of tests would enter the market through the precertification program, and the rest would be exempt from premarket review under other provisions (e.g., low-risk exemption). This goal is ambitious and will require more detailed discussions regarding the structure of the IVCT regulatory framework in order to understand whether such a low rate of premarket approval is feasible.

That said, the efforts taken by the bill’s drafters to ease market access for IVCTs were not similarly applied to the postmarket requirements, which heavily rely on the existing postmarket framework for medical devices. LDTs have historically enjoyed fewer regulatory burdens than tests actively regulated by FDA, and attempting to apply the medical device postmarket regulations to future IVCTs could instigate push back from industry.

About The Author

Blake E. Wilson is a senior associate in Hogan Lovells’ Medical Device group. Mr. Wilson's practice focuses primarily on medical device regulatory matters, with an emphasis on the premarket clearance and new medical device approval. Drawing on his industry experience in clinical research, Mr. Wilson advises clients on clinical trial regulations and use of clinical trials in FDA’s premarket review process. Mr. Wilson obtained his Juris Doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania Law School, along with a Certificate in Business Economics and Public Policy from the University of Pennsylvania, Wharton School of Business.

[i] Eligible for exemption from premarket approval. To be eligible, must demonstrate that <8,000 patients in US would be subject to test per year.

[ii] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Technical Advice on VALID Act of 2018 (Apr. 5, 2019) accessed June 17, 2019

[iii] https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/FDAVoices/ucm627742.htm