How To Respond To A Failed Batch In A Virtual Supply Chain

By Hal Craig, Trout Creek Consulting, LLC

You just received the urgent call, email, or text that a batch of commercial product made by your company’s outsourced supply chain has failed and, at first glance, the failure isn’t due to an analytical error. What do you do next?

This article provides some insights on how to approach a failed batch for an NDA/ANDA product with an emphasis on finding and resolving the root cause of the failed batch.

First Things First — Wits, Facts, Priorities, And Team

Keep your wits about you, don’t panic, and don’t jump to conclusions. Many of you probably know NASA flight director Gene Kranz’s statement about Apollo 13: “Let’s work the problem, people. Let’s not make things worse by guessing.” This is equally applicable to a failed batch.

Note the facts of the first report that you receive:

- Who is reporting the failed batch?

- How do they know the batch failed? What metric did it fail on?

- Where is the batch in the supply chain? Has it been distributed to pharmacies and patients?

- When did they know the batch failed?

- How many batches are affected?

These are crucial facts because they will give you a first impression of whether patients are at risk, if a Field Alert Report (FAR) should be filed with the FDA, and if a recall is likely.

Understand your priorities because in a crisis or near-crisis situation there may be decision trade-offs. Each company may have its own view on priorities; here are mine for a failed commercial batch:

- It’s about the patients. The reliable supply of safe and effective life-improving medicines is the top priority. This means protecting patients and eliminating the failure cause so that product production and patient treatment may resume.

- It’s about the regulators. Regulatory filings may be required, and investigations and associated records will certainly be needed. You want the FDA, other relevant regulatory bodies, supply chain partners and customers, and employees to know that your company clears a high bar for quality, compliance, and responsiveness.

- It’s about your business and brand. Eliminating the cause of failure, earning trust, reliably supplying safe and effective medicines, and appropriate external communications are key.

Identify the core internal team that is going to investigate and resolve this problem. Clearly, quality assurance, regulatory, and technical operations/supply chain should be involved. Depending on the failure metric, R&D will be, too. If the failure involves distributed product or might cause a drug shortage, then commercial, medical affairs, finance, legal, and other functions might also be on the team. Pick a team leader who will drive the investigation, resolution, cross-functional/cross-organizational communication, and provide cogent communication with your executive team.

Include outsourced partners on the team. While it does depend on the failure metric, assume that the drug product CMO will be on the team investigating the root cause. Other suppliers may also be involved in the investigation and resolution; the third party logistics firm and distributors will be involved in recalls and other customer/patient-facing actions. Be sure to understand inventory levels and whether forecasts and purchase orders need adjustment.

Have regular team update calls, weekly if not daily. Even an update saying “we’re on track to have results from task X tomorrow morning” is better than no report.

Resist the temptation to play the “blame game.” You need your supply chain partners to help find and resolve the cause of the batch failure as well as to grow your business. If indeed the root cause was negligence, willful misconduct, or another cGMP violation, the provisions of the supply and quality agreements will cover this in due time.

Regulatory Aspects

Regulatory requirements1 somewhat depend on whether the failed batch has been distributed. Briefly, if a failed NDA or ANDA batch has been distributed, or if the investigation into the failure of an undistributed batch indicates a failure of one or more distributed batches, then according to 21 CFR 314.81(b)(1) and 314.98(b), a FAR must be submitted to the FDA within three working days of receiving the following information for a distributed drug product:

- Information concerning any incident that causes the drug product or its labeling to be mistaken for, or applied to, another article

- Information concerning any bacteriological contamination, or any significant chemical, physical, or other change or deterioration in the distributed drug product, or any failure of one or more distributed batches of the drug product to meet the specification established for it in the application

Note that the NDA/ANDA applicant is responsible for submitting the FAR, even in an outsourced supply chain.

Along with FAR requirements, it is worth noting recall classifications:2

- Class I: A dangerous or defective product that could cause serious health problems or death

- Class II: A product that might cause a temporary health problem or pose slight threat of a serious nature

- Class III: A product that is unlikely to cause any adverse health reaction, but that violates FDA labeling or manufacturing laws

According to 21 CFR 211.192, “the failure of a batch…to meet any of its specifications shall be thoroughly investigated, whether or not the batch has already been distributed. The investigation shall extend to other batches…that may have been associated with the specific failure...” Further, 21 CFR 211.198 states “Where an investigation under 211.192 is not conducted, the written record shall include…the name of the responsible person making such a determination.” There are regulatory requirements and accountability associated with investigations.

Solving The Problem

A batch can be failed for many reasons or symptoms. Here is a partial list of symptoms derived from the FDA’s recall database: contamination (microbial or other type); cGMP deficiencies; particulates; incorrect package label or improper product in the package; failed stability specification; out of temperature storage; cracked or broken capsules; potency; and adverse events. Some symptoms have readily definable causes and fixes. Others are not so definable and could lead to a new design space or a new supplier if achieving the desired level of quality is not possible.

Here is one approach for finding more challenging root causes of failed drug product, drug substance, or raw material batches:

- Confirm the analytical results. If the batch failure is based on an analytical result, confirm that:

- Sampling, sample preparation, and sample testing occurred correctly.

- Calibrated instrumentation, clean glassware, and properly maintained reference standards were used.

- Properly trained, experienced personnel were following the validated analytical method.

- If it is an analytical error, the erroneous result must be scientifically invalidated.

- Identify what has changed. Review batch, raw material, analytical testing, and equipment and facility cleaning/maintenance/calibration/use records for both the failed batch(es) and acceptable batches made before and after the failed batch(es) to identify what changed. Was there a new raw material lot, a different person performing the work, or equipment maintenance before the failed batch? Was there a unique situation where one raw material was at the low end of its specification range while another raw material was at the high end of its range?

- Determine when change occurred. The root cause of the batch failure might be a change that occurred several batches or even weeks before the first batch failure. Check control charts and process capability indices to determine when the manufacturing process first began to change. Once the “when” is known, it is easier to find the “what.” Maybe the “what” was a new utility system or new process equipment or instrumentation? Maybe it was a process change at a raw material supplier?

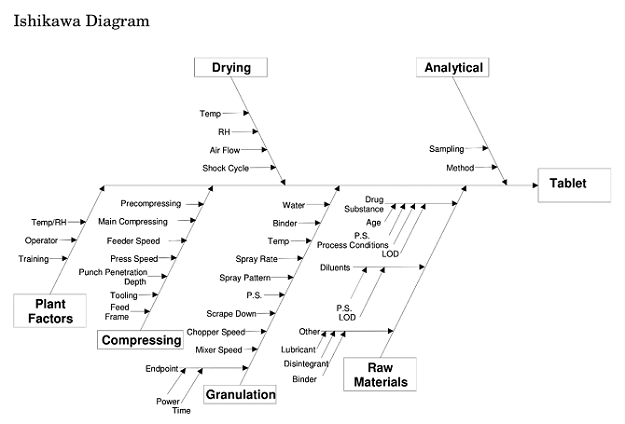

- Use an Ishikawa Diagram. Fishbone diagrams, such as this one from ICH Q8(R2),3 are incredibly helpful in identifying possible causes. Remember to use categories appropriate to your situation.

- Understand the underlying science. Certainly know the chemistry and physics behind the manufacturing process and product. Search the literature to see if the issues your process or product encountered have been found with similar chemicals or equipment elsewhere.

- Have non-cGMP small scale testing capability. Having the ability to test both causation and resolution theories quickly and inexpensively is very important.

Once the root cause and its resolution (CAPA) have been found and demonstrated, they need to be communicated and incorporated into everyday production. Some root causes, such as the incorrect installation of a new sieving screen, are relatively easy to correct through training and having an additional person check the installation. Other root causes, such as the lack of a sufficiently robust quality culture at a supplier, are clearly more difficult to fix. Proactive supplier auditing, contracts with change control and related provisions, a quality risk management process, and engaging key suppliers for mutual understanding of the critical quality attributes to be achieved at each supplier are important tools to prevent failed batches.

Remember to work the problem and not go into an investigation with a “Who is to blame and who is going to pay for this?” attitude. The goal is to supply life-improving medicines to patients and to keep your business on track. To do this, the drug marketer needs a transparent and cooperative supply chain that will quickly respond to issues and deliver. Focus on finding the root cause of the batch failure, the resolution of that root cause, and helping patients. Once the facts are known, let the provisions of the various contracts between the drug marketer and its suppliers govern.

References:

- Field Alert Report Submission, Questions and Answers, Guidance for Industry, Draft Guidance, U.S. FDA, July 2018

- FDA’s Role in Drug Recalls, https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugRecalls/ucm612550.htm, last updated July 5, 2018

- Q8(R2) Pharmaceutical Development, Guidance for Industry, U.S. FDA, November 2009

About The Author:

Hal Craig is the founder of Trout Creek Consulting, LLC, a strategy and life science supply chain consultancy focused on solving CMC, outsourcing, strategy, and technical challenges. Clients include venture-backed, family-owned, private equity-owned, and publicly traded companies. Mr. Craig serves on the Physical Sciences Investment Advisory Committee of Ben Franklin Technology Partners of Southeastern Pennsylvania. He has a BSChE from the University of California, Berkeley and an MBA from the University of Michigan. He can be reached at hcraig@troutcreekconsulting.com.

Hal Craig is the founder of Trout Creek Consulting, LLC, a strategy and life science supply chain consultancy focused on solving CMC, outsourcing, strategy, and technical challenges. Clients include venture-backed, family-owned, private equity-owned, and publicly traded companies. Mr. Craig serves on the Physical Sciences Investment Advisory Committee of Ben Franklin Technology Partners of Southeastern Pennsylvania. He has a BSChE from the University of California, Berkeley and an MBA from the University of Michigan. He can be reached at hcraig@troutcreekconsulting.com.